Who lost when the Jaragua crumbled?

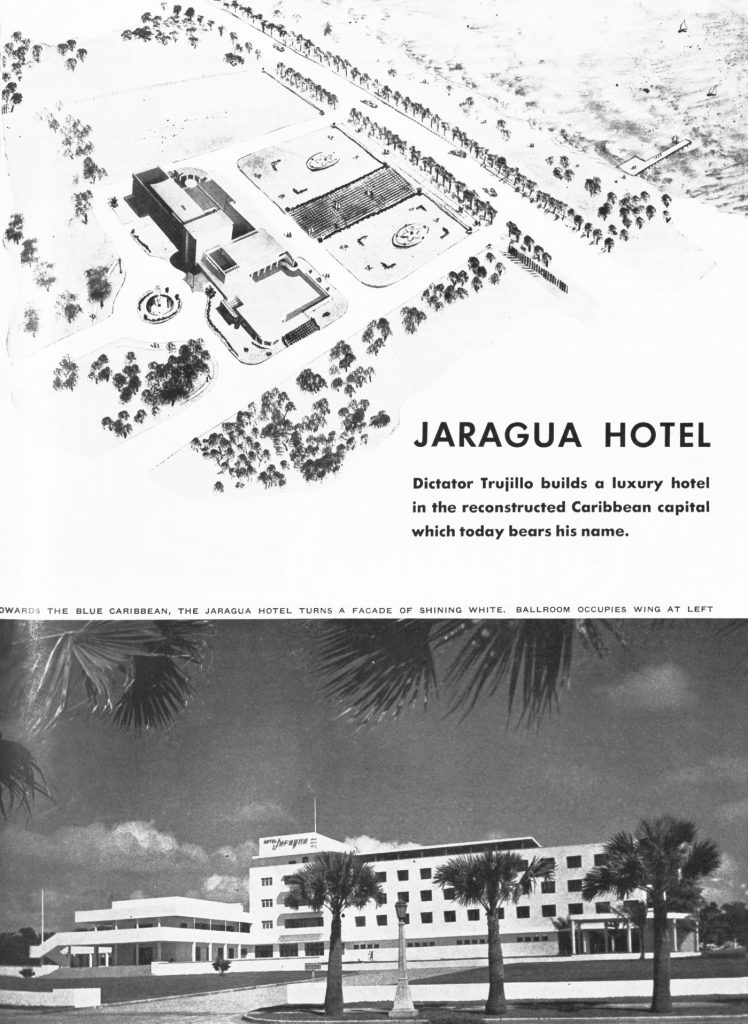

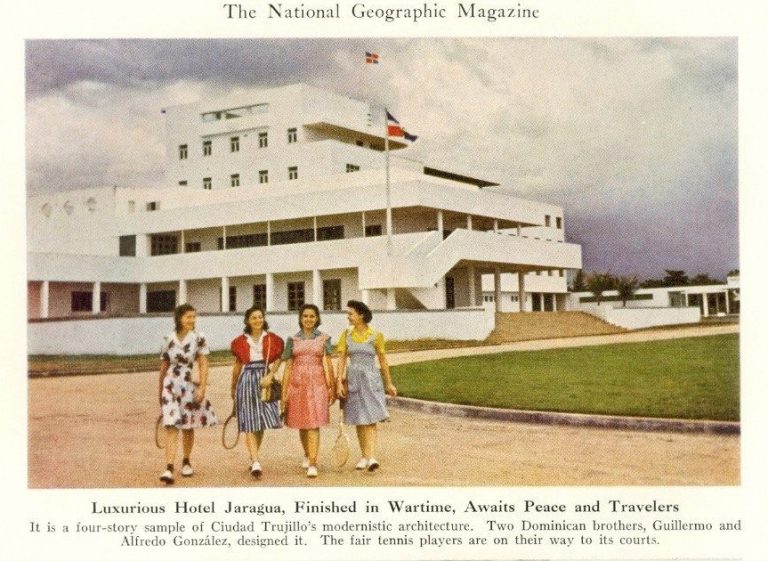

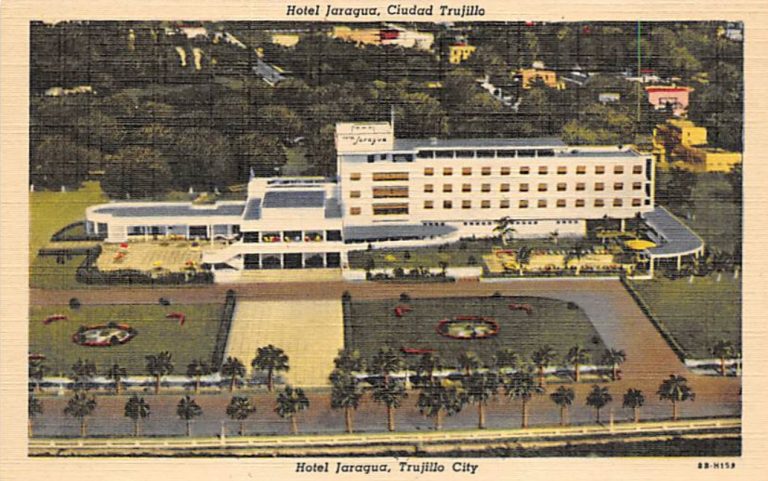

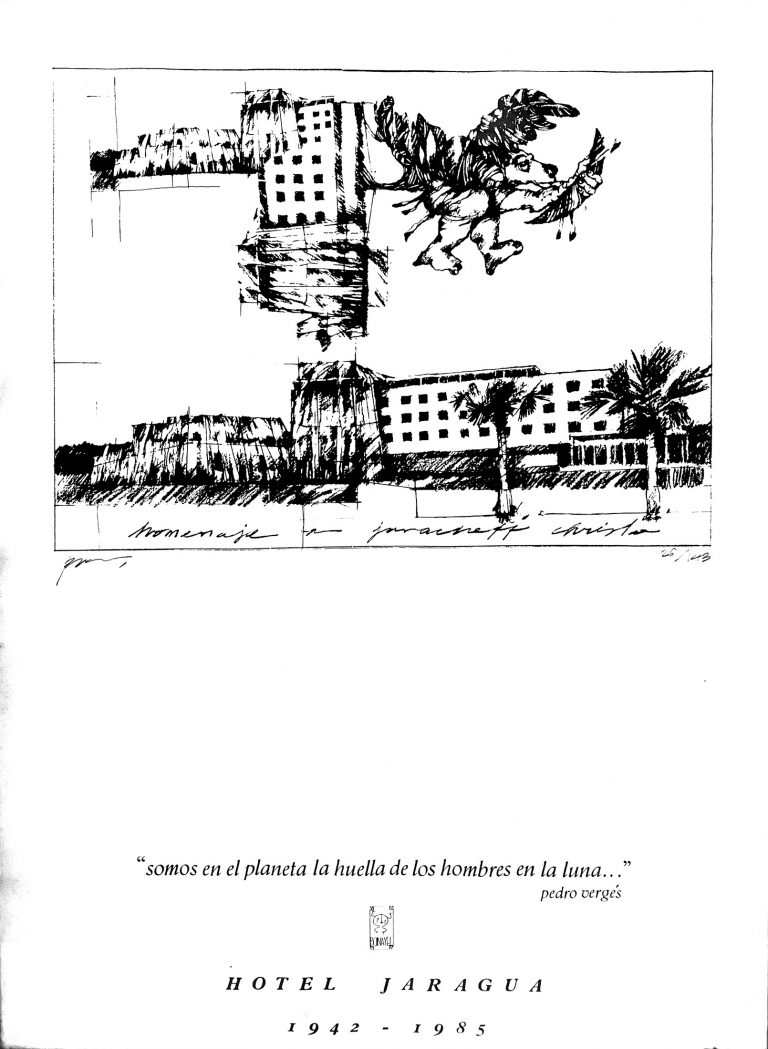

The Dominican Republic still wasn’t the travel destination it has eventually become when a landmark event marked the spot between dreaming and doing: in 1942 the capital city built its first large-scale hotel, across the Caribbean Sea, letting the entire world know the country was ready to welcome it with open arms.

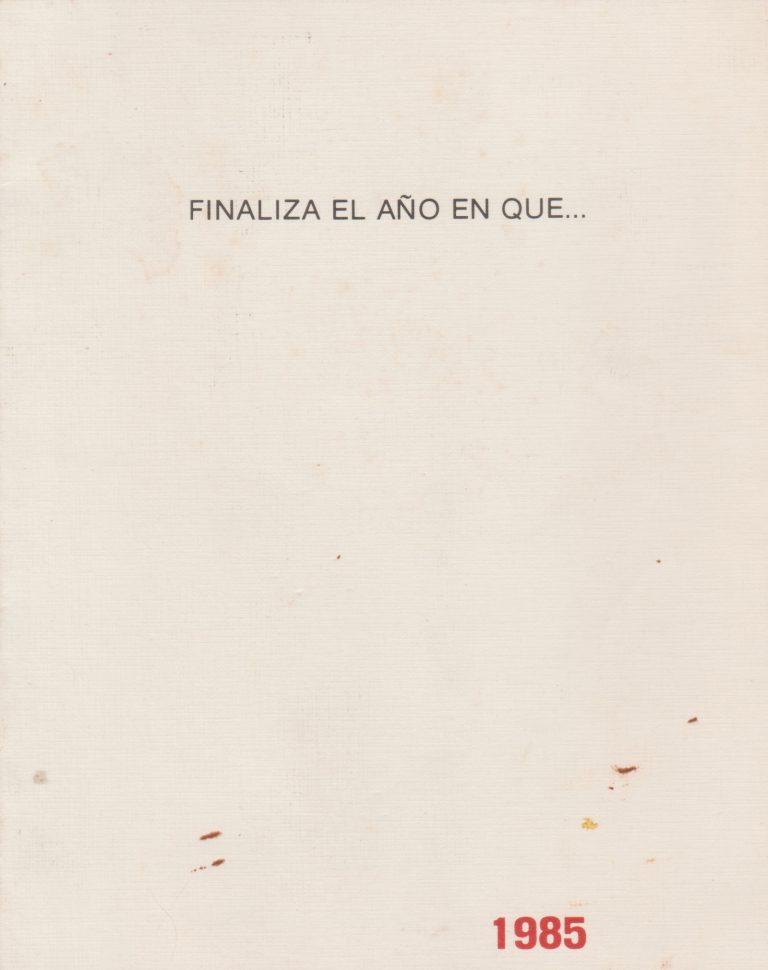

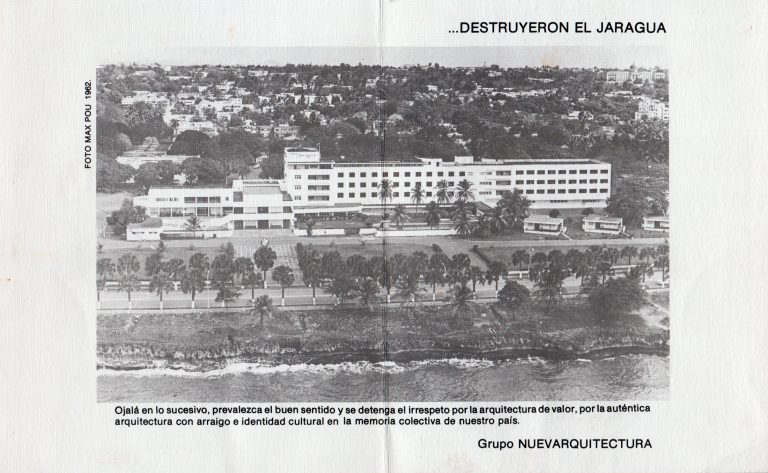

And this wasn’t just any hotel: it was the first venue of its kind in the entire region, a rationalist structure that challenged the established hospitality typology in the Antilles and spoke of a small country looking towards a brighter future. In 1985, surrounded by protests and a large social melee, the Jaragua Hotel was torn down.

Between its birth at the hands of the megalomaniac dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo Molina and its death during the murky rule of Salvador Jorge Blanco, what value did Dominicans see in the hotel? Did we know what we were losing? Or what’s more: Are we currently suffering the consequences of the downfall of what probably was the most important work of modernist architecture in the country?

THE CITY

Up until September 3, 1930, Santo Domingo was not the firm city one would expect from the first Spanish colony in the Americas, but one built out of wood: most of the houses were made out of planks, zinc and palm leaves. After the cruel ravage of Hurricane San Zenón, the capital was leveled; the only witnesses left standing were the manors the Spaniards left behind and a handful of houses of recent build. Which ones, in particular? Those created using reinforced concrete, a then little-known technique amongst the locals that had been used successfully in the city center of the buoyant San Pedro de Macorís.

-

The state of Santo Domingo after the wrath of Hurricane San Zenón in 1930 (Source: AGN)

-

The state of Santo Domingo after the wrath of Hurricane San Zenón in 1930 (Source: AGN)

-

The state of Santo Domingo after the wrath of Hurricane San Zenón in 1930 (Source: AGN)

-

The state of Santo Domingo after the wrath of Hurricane San Zenón in 1930 (Source: AGN)

Santo Domingo starts having some concrete thoughts

-

Osvaldo Báez's Padre Billini Hospital, built in Santo Domingo in 1925 (Source: AGN)

-

Francisco Caro's chalet in Santo Domingo, designed in 1935 by José Antonio Caro (Source: Caro Family Archives)

-

The 1935 Fernández Building, designed by José Antonio Caro and Leo Pou Ricart in Santo Domingo (Source: Caro Family Archives)

-

Leo and Marcial Pou Ricart's Instituto de Señoritas Salomé Ureña, built in Santo Domingo between 1943-1944 (Source: AGN)

-

The 1936 Steam House, designed by Henry Gazón Bona in Santo Domingo (Source: AGN)

-

Parque Independencia in Santo Domingo in the 1940s (Source: AGN)

-

Panoramic view over Columbus Park and Santo Domingo's City Hall in the 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

Panoramic view over Santo Domingo's harbor and its concrete wall in the early 1940s (Source: AGN)

-

Sundt & Wenner's First Evangelical Church of Santo Domingo, built between 1933-1936 (Source: AGN)

THE MATERIAL

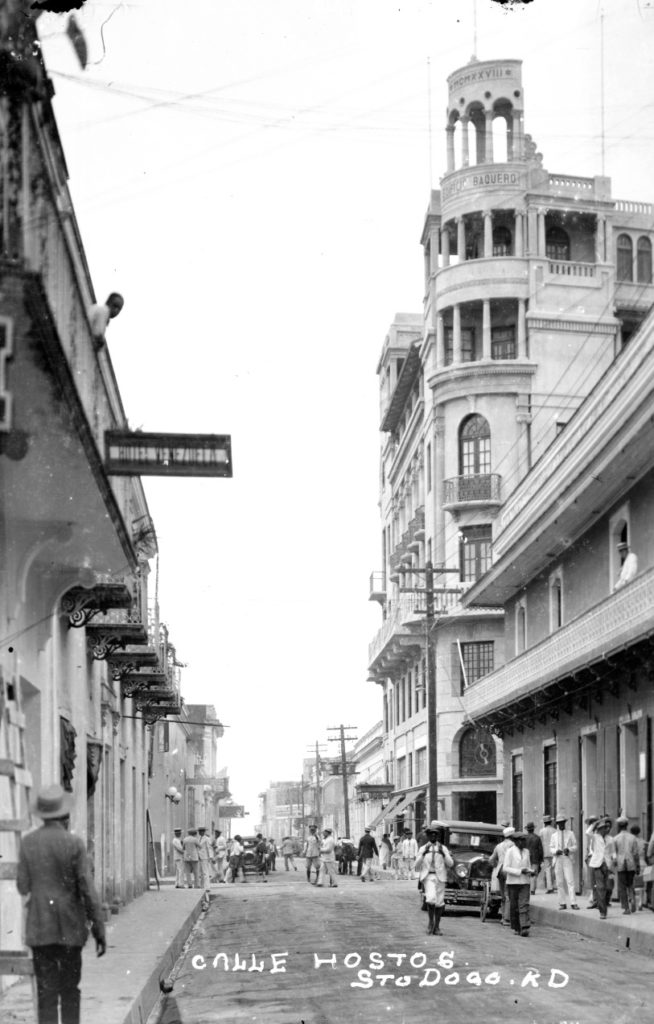

The hurricane had another strong force waiting on the other side. In August of 1930 a product of the police and military forces had taken control of the country: General Rafael Molina Trujillo. San Zenón gave the newly minted president the chance to rebuild a capital that would speak of the strength of his government… and the only way to do so was by using reinforced concrete. Thus swiftly, Santo Domingo started having some concrete thoughts —and building accordingly. That’s when the city started seeing works that reflected the technical prowess of the 20th century: 1927’s Baquero Building —an eclectic neoclassical structure that was one of San Zenón’s few survivors— was joined by the likes of the Fernández Building, an art déco project created by José Antonio Caro and Leo Pou Ricart. Other newcomers were the city’s first Evangelical church, built by Benigno de Trueba and Eric Mayer on Las Mercedes Street, as well as the eye-catching Casa Vapor by Henry Gazón Bona. Thanks to these arrivals in quick succession, Santo Domingo started seeing a modern Caribbean city staring back in the mirror.

The Caribbean Sea starts claiming its rightful place

THE SEA

Santo Domingo didn't think of the Caribbean Sea as a spot made for leisure: in the past, that's where pirates came from; in the present, that's where the stench of the slaughterhouse originated. Certainly, many wealthy families had lots by the coastline that were used as weekend homes, but the water was such an aftertought that the villas used to face the Camino del Oeste —that is, today's Independencia Avenue. Nevertheless, in 1936 one of Trujillo's projects created a seaside esplanade that allowed locals to think of the new promenade as the ideal place to go and do nothing. It's just that, given that grand container, where was the content?

-

George Washington Avenue in Santo Domingo in the late 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

George Washington Avenue in Santo Domingo in the late 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

George Washington Avenue in Santo Domingo in the late 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

George Washington Avenue in Santo Domingo in the late 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

George Washington Avenue in Santo Domingo in the late 1930s (Source: AGN)

Who will be in charge of designing our future?

-

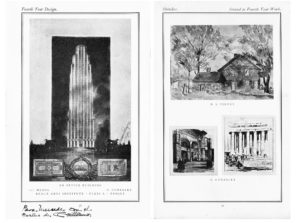

Drawings by Guillermo González included in the 1929-1930 Bulletin of Yale University - School of Fine Arts (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

-

Cover of the 1929-1930 Bulletin of Yale University - School of Fine Arts (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

-

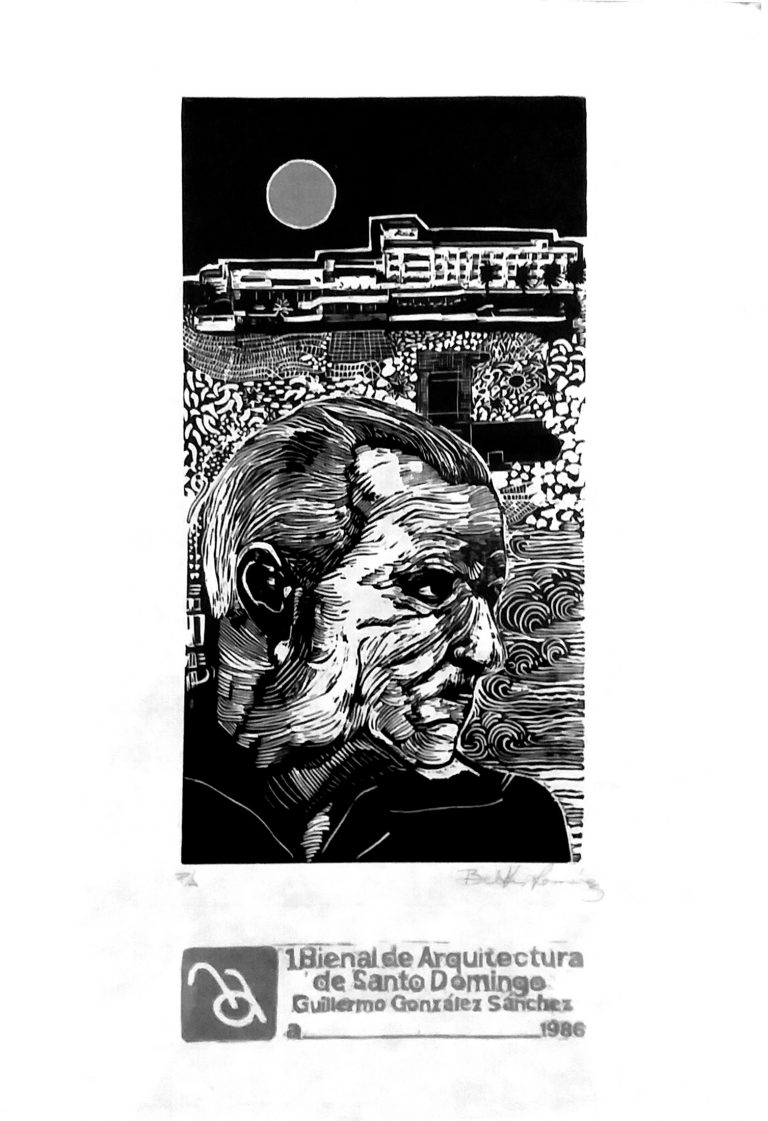

Guillermo González in the 1920s (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

-

Guillermo González's Schad House, built in Santo Domingo in 1940 (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González in the 1930s (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

-

Guillermo González in the 1920s (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

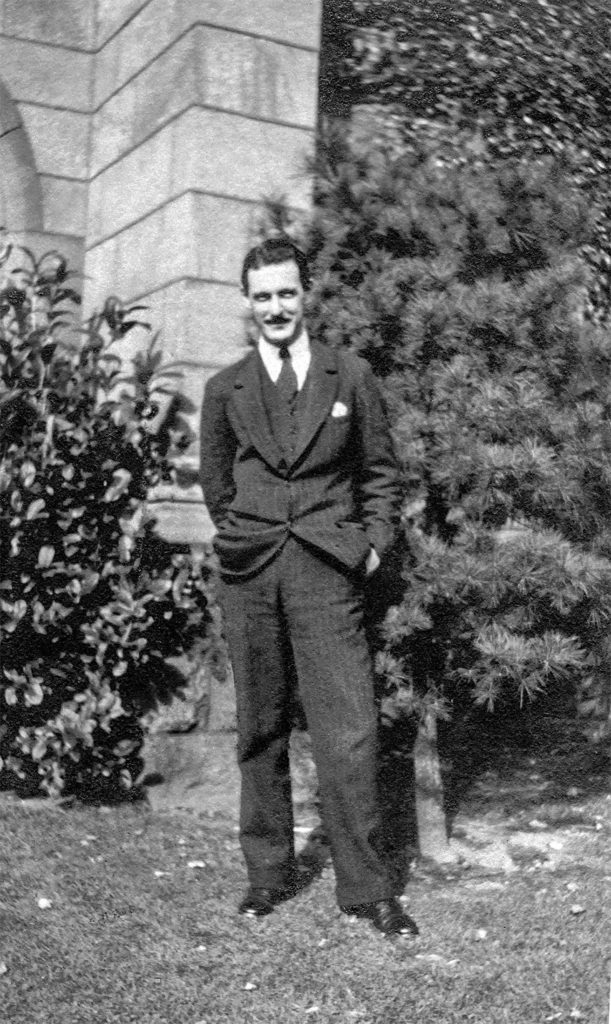

THE ARCHITECT

Back then, the University of Santo Domingo didn't offer a BA in Architecture. That explains why a young draftsman at the Design Office of the General Authority for Public Works had set his sights on the East Coast of the United States: his goal was to gain admission to the Department of Architecture at Yale. After a stint at Columbia's fine arts school and also at several of New York's architecture firms, he was finally able to enroll at the Connecticut university —on probation, though, as his record showed a trail of academic and professional experience in fits and starts. Against the expectations of the admissions department, he would go on to graduate at the top of his class, claiming several student awards in his wake. After graduation, he embarked on a grand tour of Europe in order to better train his eye: Paris, Rome and Madrid were on his itinerary, and there he absorbed several years' worth of stylistic education in a matter of months. Back home in 1932 he went on to design a few residences, such as Rancho Cayuco, a Spanish Revival home occupied by Porfirio Rubirosa and Flor de Oro Trujillo —that is, the dictator's daughter. In fact, having a Trujillo as a client would become some sort of future leitmotiv: between 1939 and 1956 architect Guillermo González would go on to produce some of the most iconic public buidlings of the era.

Ramfis, Copello and Columbus

THE DICTATOR

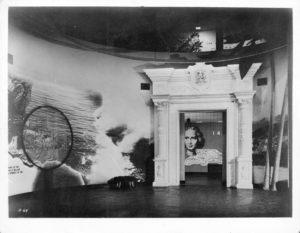

The city made an open call for proposals for a children's park —which would be named after the dictator's son, nicknamed Ramfis— overlooking the coastline. Among them, one in particular stood out due to its rationalist model with clean lines, which seemed to dive into the sea: Guillermo González's. Opened in 1937, the Ramfis Children's Park showed citizens —and their young— the joys of relaxing across the Caribbean Sea. Impressed by his skills, the dictatorship would also hire González to create the Dominican Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair —a display eventually titled

-

Guillermo González's Copello Building, built in Santo Domingo in 1939 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

Guillermo González's Copello Building, built in Santo Domingo in 1939 (Source: AGN)

-

The Dominican Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed by Guillermo González (Source: AGN)

-

The Dominican Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed by Guillermo González (Source: AGN)

-

The Dominican Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed by Guillermo González (Source: AGN)

-

The Dominican Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed by Guillermo González (Source: AGN)

-

The Dominican Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed by Guillermo González (Source: AGN)

-

A May 2, 1939 Listín Diario clipping on the Dominican participation in the 1939 New York World's Fair (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González's Ramfis Children’s Park, built in Santo Domingo in 1937 (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González's Ramfis Children’s Park, built in Santo Domingo in 1937 (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González's Ramfis Children’s Park, built in Santo Domingo in 1937 (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González's Ramfis Children’s Park, built in Santo Domingo in 1937 (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González's Ramfis Children’s Park, built in Santo Domingo in 1937 (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González's Ramfis Children’s Park, built in Santo Domingo in 1937 (Source: AGN)

A hotel up to Ciudad Trujillo's standards

-

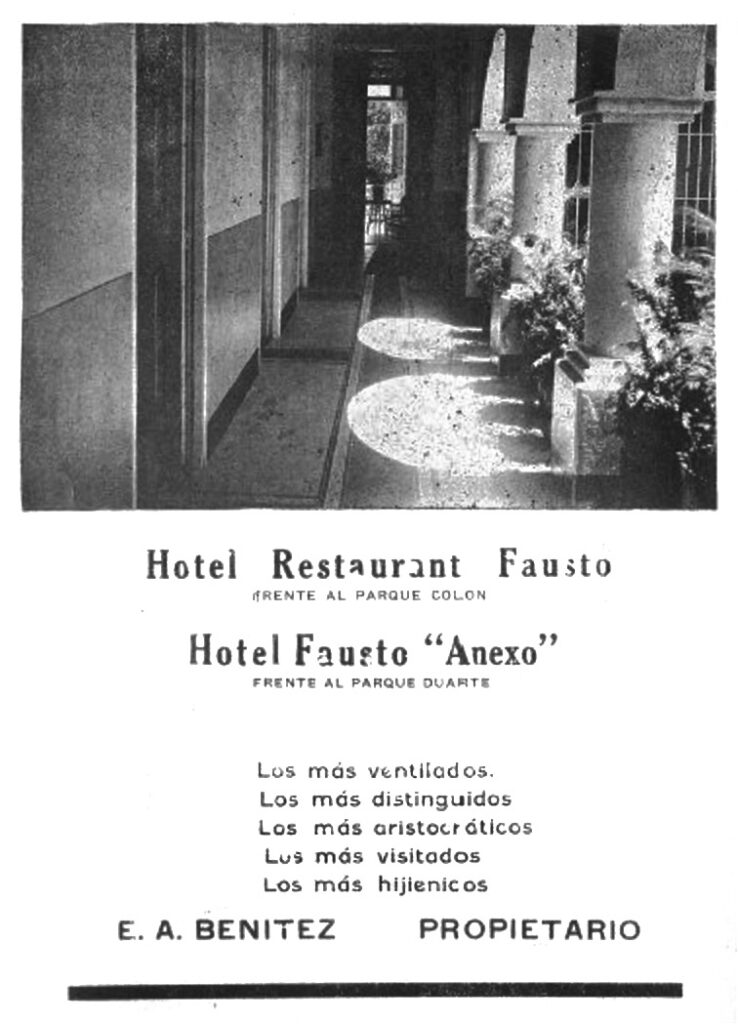

An ad for the Gran Café-Restaurante y Hotel Fausto in Santo Domingo in the 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

An ad for the Gran Café-Restaurante y Hotel Fausto in Santo Domingo in the 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

A guestroom at the Gran Café-Restaurante y Hotel Fausto in Santo Domingo in the 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

The banquet hall at the Gran Café-Restaurante y Hotel Fausto in Santo Domingo in the 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

The Hotel Presidente in Santo Domingo in the 1930s (Source: AGN)

-

A postcard of the Hotel Nacional de Cuba in Havana (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

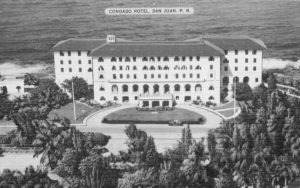

A postcard of the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

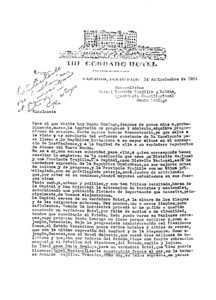

A letter from Pedro Agudo, the manager of the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel, addressed to Rafael L. Trujillo in 1934 (Source: Lidia León Archives)

-

A letter from Pedro Agudo, the manager of the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel, addressed to Rafael L. Trujillo in 1934 (Source: Lidia León Archives)

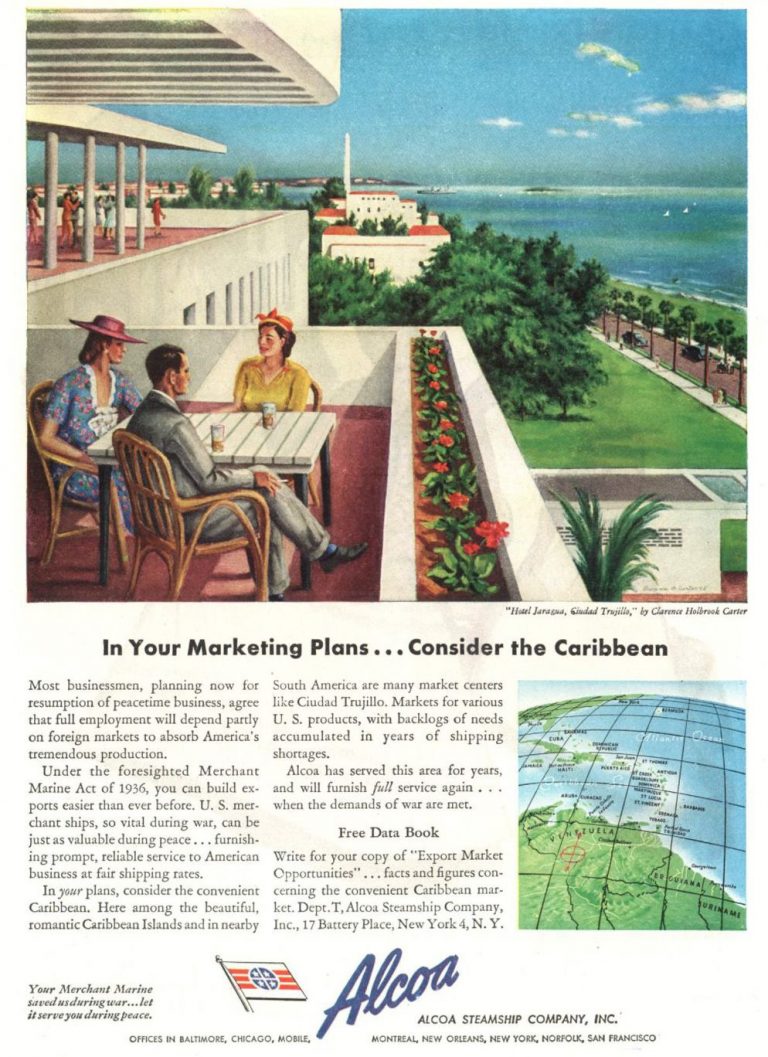

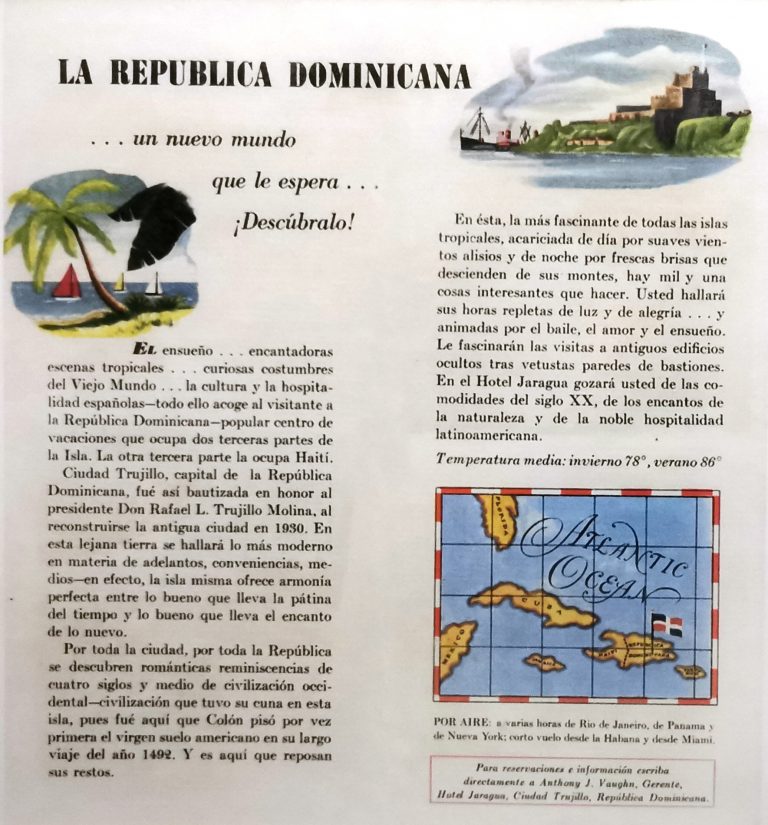

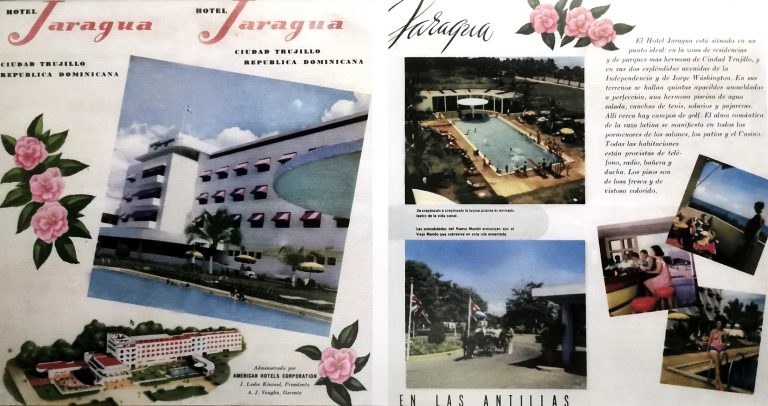

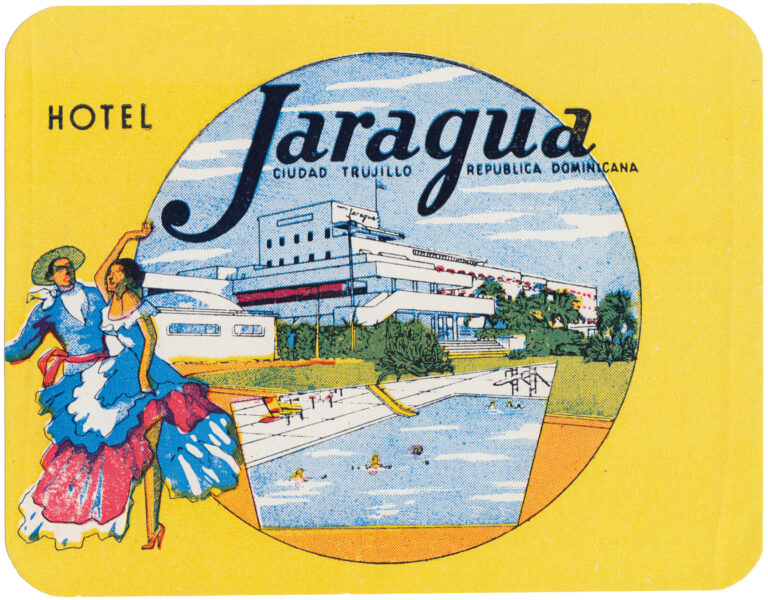

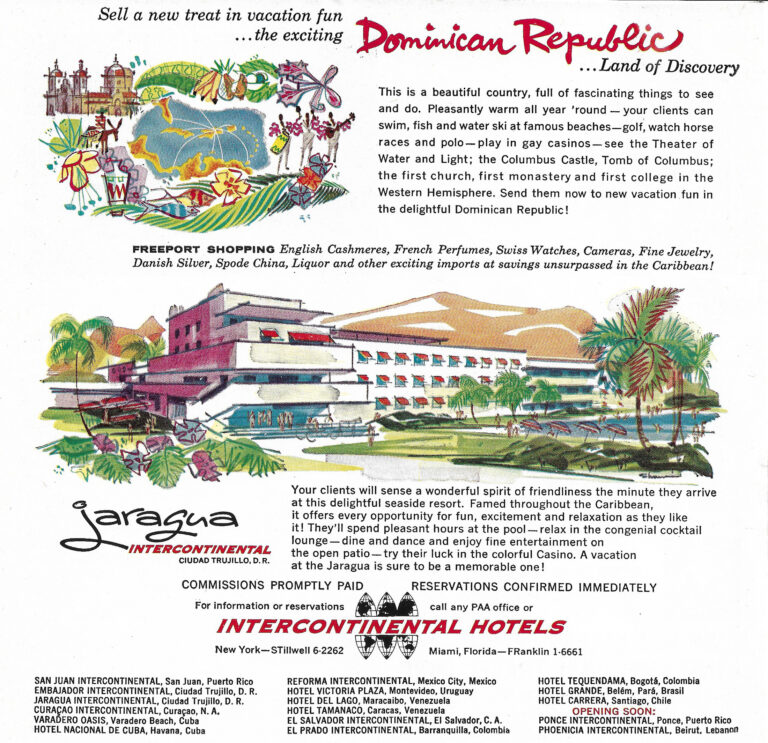

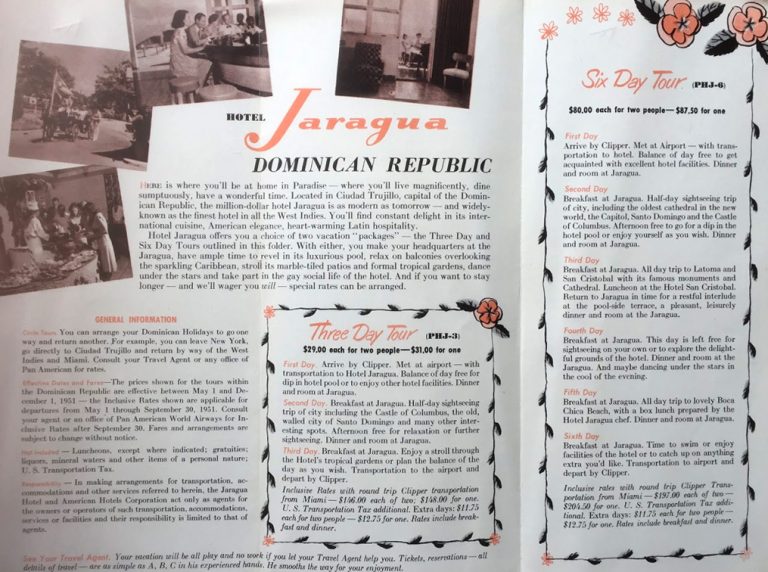

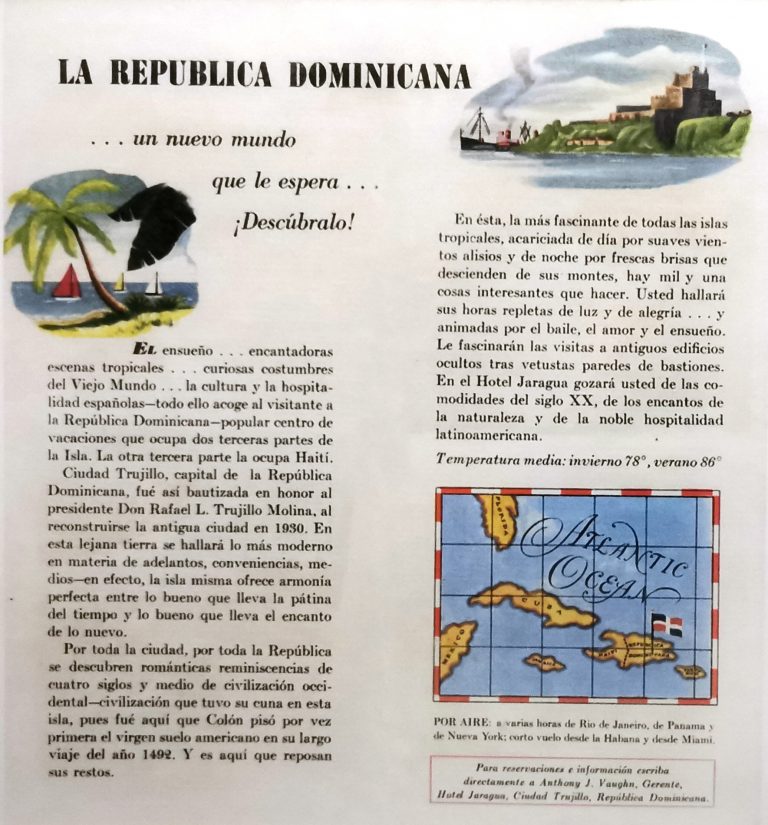

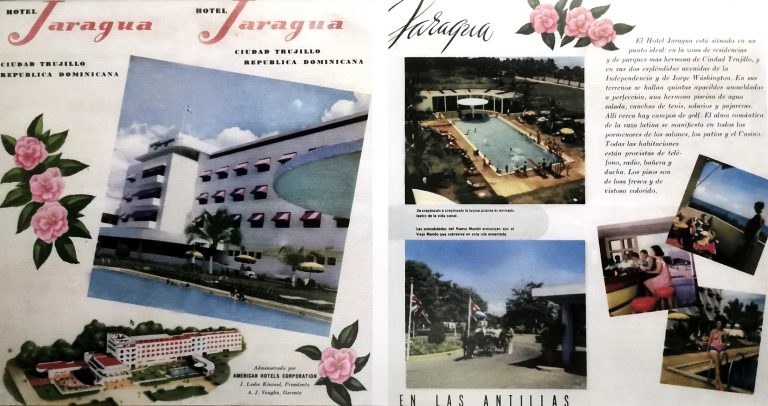

THE COMPETITION

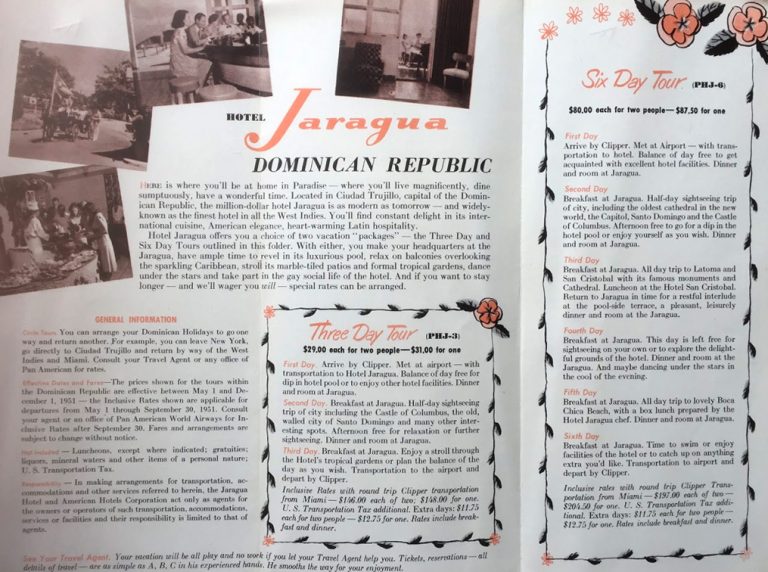

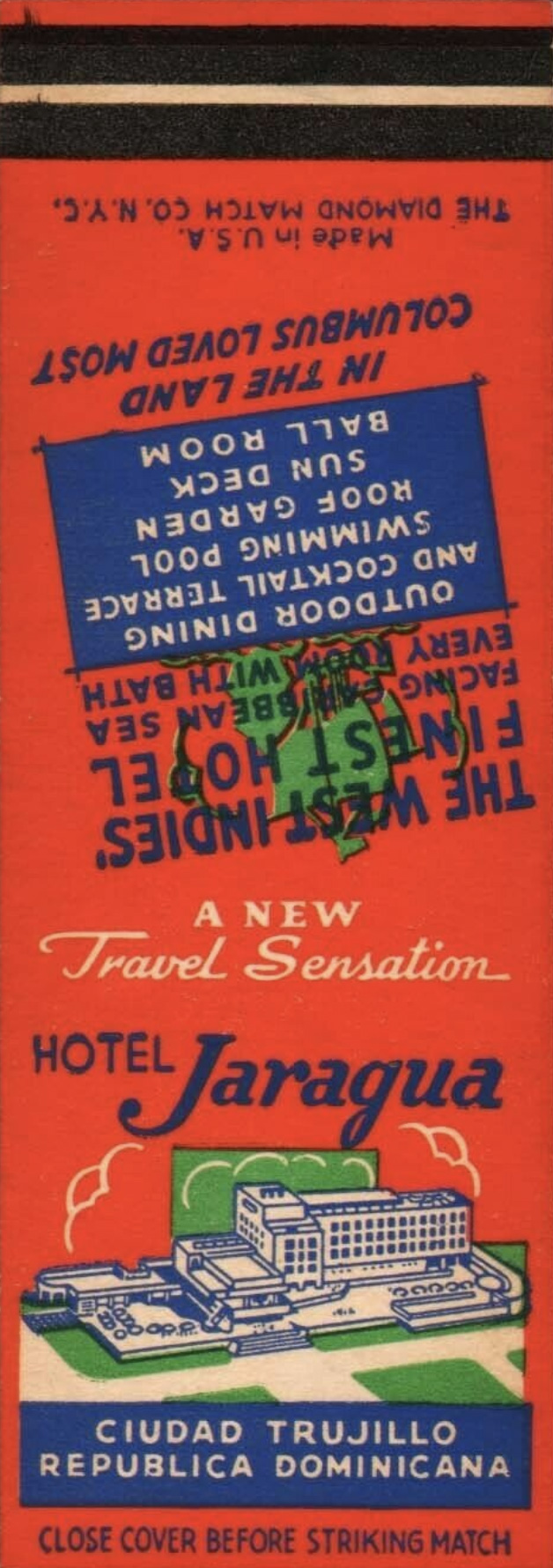

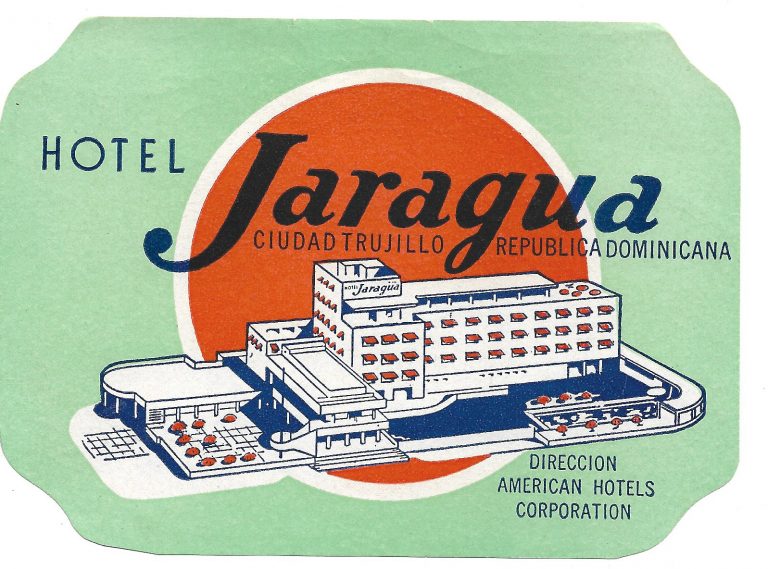

The Dominican capital —now known as Ciudad Trujillo in honor of its megalomaniac-in-chief— didn't have a strong tourism industry, and thus lacked the type of hotels that could lodge demanding travelers. At most, there were some small B&Bs and guesthouses run by inmigrant families —such as the Fausto or the Presidente. Local reality was far behind the display seen at the other two large Caribbean cities, with its Gran Condado Vanderbilt in San Juan and the Nacional in Havana. Both featured more than 100 guestrooms and a large list of social amenities that the humble dining halls of Dominicana had trouble even imagining. But that would soon change: Trujillo was doubly inspired by a visit to New York City's Waldorf Astoria and a letter from the manager of the Condado hotel suggesting the creation of a hotel that would rise to the city's new reality. According to official statements, Dominicans were in for an innovative surprise. And they were right: that new hotel on George Washington Avenue would come to challenge the hospitality universe in the Antilles.

There's something sketchy behind the scenes

THE SWINDLE

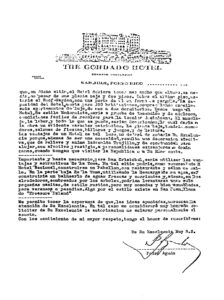

President Trujillo and his third wife, María Martínez, would never waste a chance to increase their net worth. That's why, as the hotel needed a lot to be built on, Martínez went to work: she bought a portion of the land previously known as Estancia El Carmelo, and through a front man —a British subject named Hallet Hansard— sold it to the Dominican government. In order to finance the project, local authorities requested a 400-thousand-dollar loan from America's ExIm Bank... but it's just that Guillermo González and his brother Alfredo, a civil engineer, in fact delivered a quote for 200 thousand. After the dust cleared, the Trujillo marriage ended up some 200 thousand dollars richer.

-

Independencia Avenue in Santo Domingo, formerly known as the Camino del Oeste (Source: AGN)

-

A postcard of the Road to Güibia in Santo Domingo (Source: AGN)

-

Damián Báez's ranch, located on Independencia Avenue in Santo Domingo, in an 1871 sketch by James Taylor (Source: AGN)

-

María Martínez de Trujillo and Rafael L. Trujillo in Santo Domingo in the 1940s (Source: AGN)

-

The residence permit of British subject Hallet Hansard (Source: AGN)

-

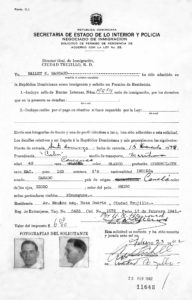

Map of the city of Santo Domingo in 1900, by Casimiro de Moya (Source: AGN)

-

Going up, five stories high

-

Construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González supervises the construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González supervises the construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Guillermo González supervises the construction process of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

-

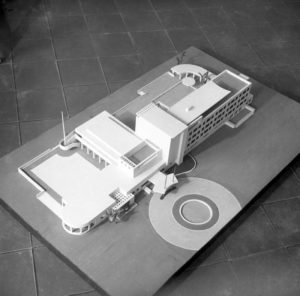

A scale model of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

A scale model of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

A scale model of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

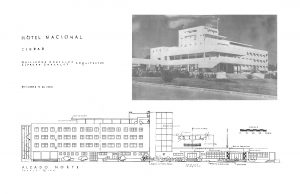

THE STRUCTURE

The actual building process was a joint endeavor between Guillermo González and his younger brother Alfredo. In a generous nine-thousand-square-meter 20-hectare lot, the architect had devoted space to the many things that the Fausto, the Francés and the other hotels in Santo Domingo failed to see as essentials. This could be clearly seen in matters of height: González's proposal rose to five stories' worth of reinforced concrete overlooking the Caribbean Sea in a west-east direction.

Is it Nacional or Jaragua?

THE NAME

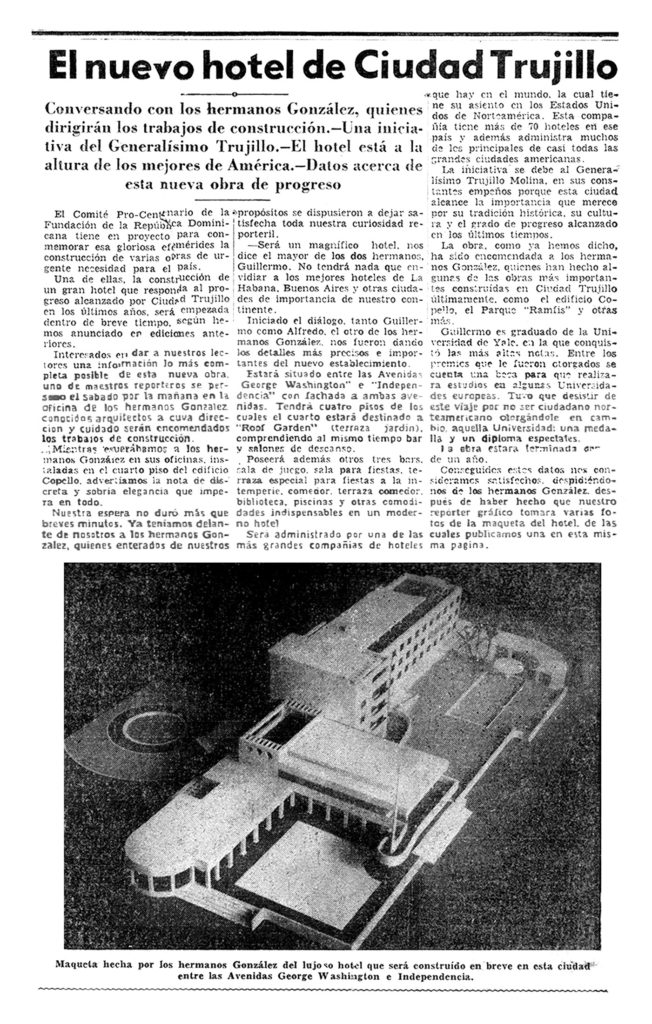

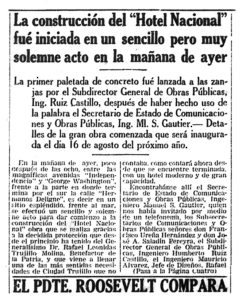

Until 1940, media references to the project spoke of

-

An August 26, 1939 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

DESCRIPTION ENGLISH

-

A July 6, 1940 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

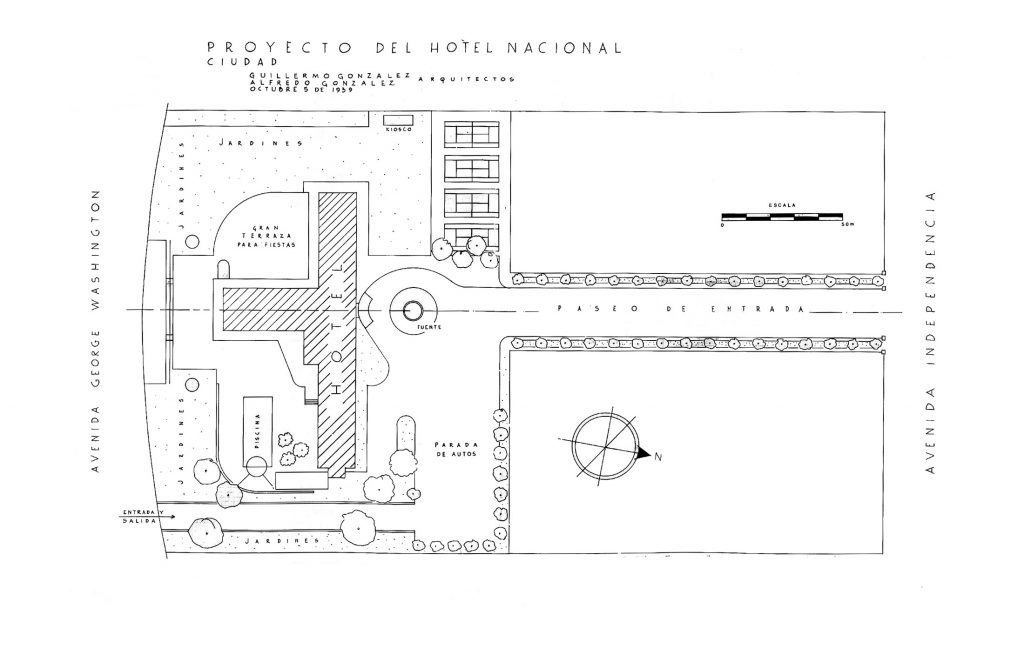

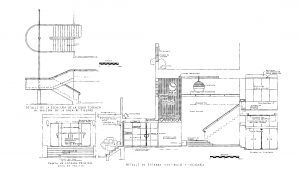

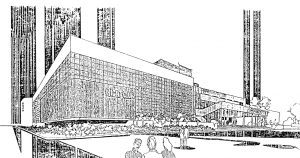

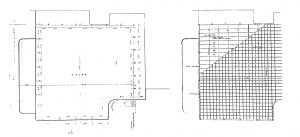

Straight from the drawing board

-

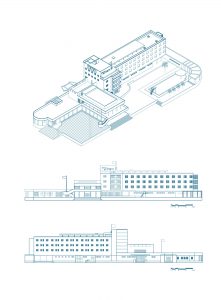

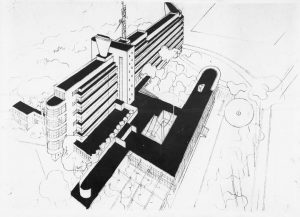

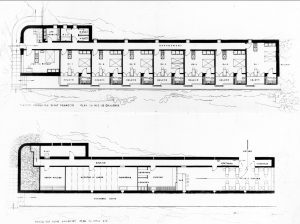

A set of architectural drawings from the Hotel Jaragua draft project, then called Hotel Nacional (Source: Dominican Architecture 1906-1950, by Enrique Penson)

-

A set of architectural drawings from the Hotel Jaragua draft project, then called Hotel Nacional (Source: Dominican Architecture 1906-1950, by Enrique Penson)

-

A sketch of the Hotel Jaragua published in the September 1946 issue of American magazine Architectural Forum (Source: Architectural Forum)

-

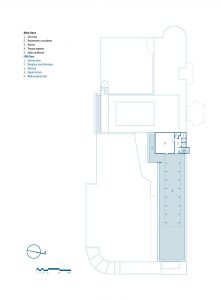

First-level floor plan of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Archipiélago)

-

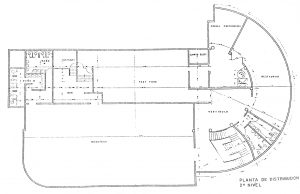

Second-floor plan of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Archipiélago)

-

Third and fourth-level standard-layout floor plan of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Archipiélago)

-

Fifth-leven floor plan of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Archipiélago)

-

Axonometric view and south and north elevations of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Archipiélago)

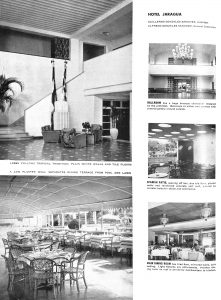

THE PROJECT

The initial blueprints for the Jaragua Hotel, signed by the González siblings, were ready for approval back in October of 1939. Those pages bore an innovative rationalist proposal with an obvious efficiency in terms of distributing its interior spaces. On top of that, it's quite surprising to see how the eldest González had a crystal-clear vision about what he wanted, as the proposal reveals a thorough level of details —for example, he had written in a minimalist clock in the lobby, floating glass doors and specific requests for finishing materials.

The cruise ship dropped anchor across the sea

THE LAYOUT

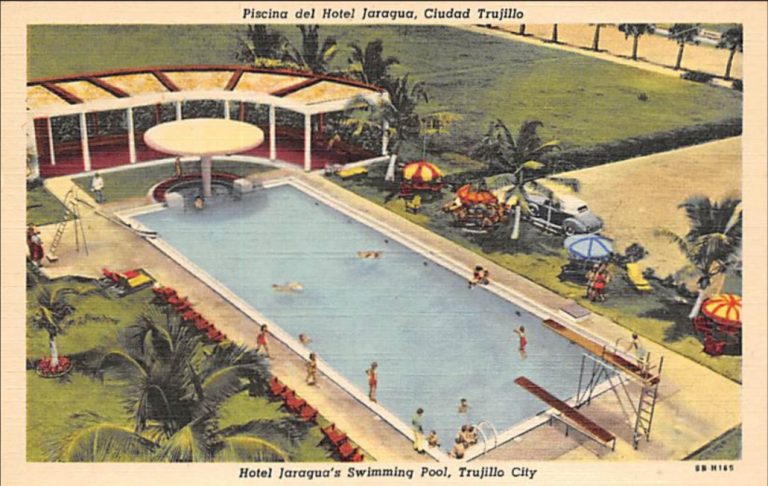

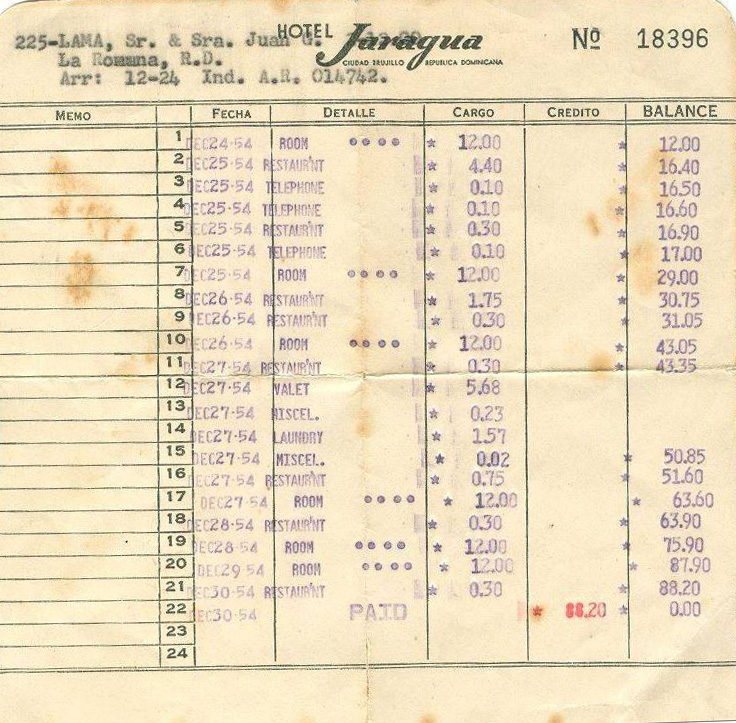

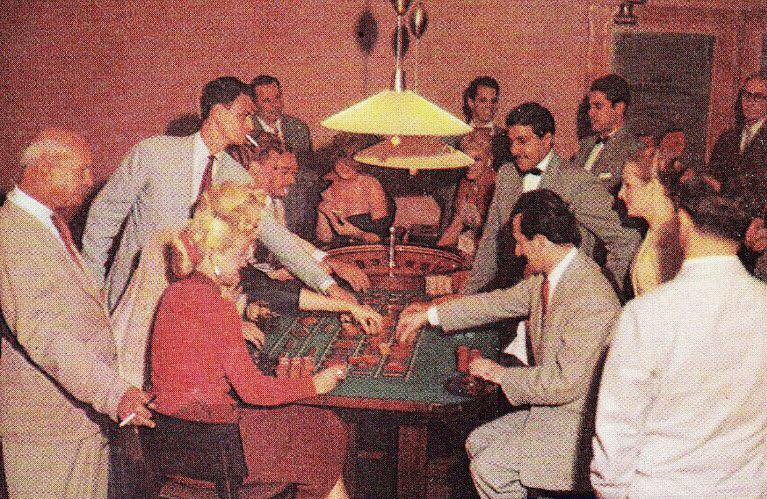

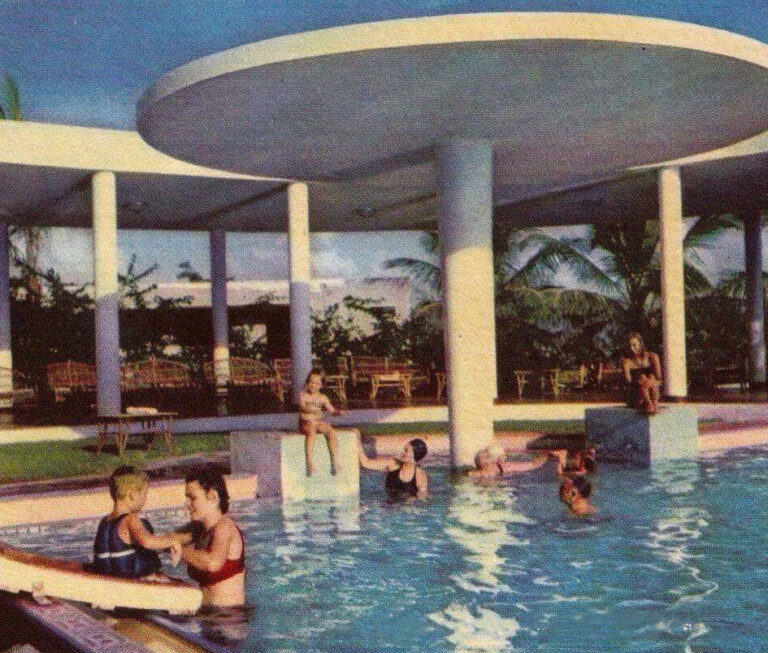

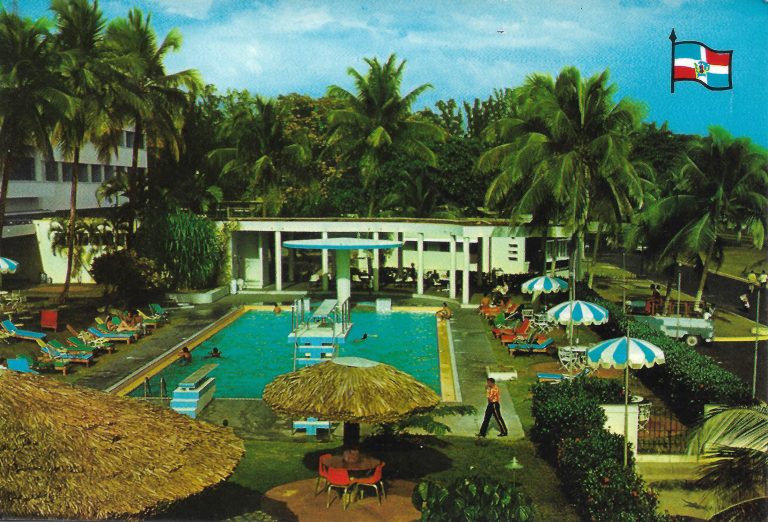

The first floor began with a driveway that led to a cathedral-ceiling lobby, featuring front-and-center a bust of Trujillo —lest anyone forget who had conceived the project. The lobby itself rose in the middle of the vertical volume, with the hotel's public areas surrounding it. For example, there was a grand ballroom to the south and a porch around three of its sides. To the west one could find a gift shop, a writing room, a beauty parlor and a casino —and the latter had its own independent entryways. The central bar connected the main terrace to the Andalusian courtyard, and to another terrace that overlooked the northern gardens. Towards the east stood a large dining hall, the kitchen, a private dining hall, laundry facilities and several service areas. Nearby one could descend to the basement, where González had placed the complementary service areas: the hot-water cauldron, the workshops and the storage rooms. Facing the sea towards the south were the gardens, the pool and the grand open-air terrace. Floors two to four featured a similar layout, with guestrooms placed on both sides of a central hallway. Single rooms faced north while double ones, overlooking the pool, faced south. Both featured ensuite bathrooms and cedar closets, as well as phones, electric ceiling fans and radios. There were 66 rooms in total —36 doubles and 30 singles— and three suites.

-

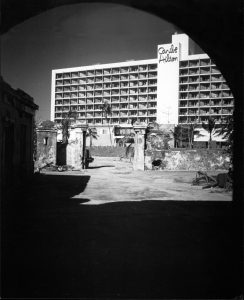

Southern façade of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Southern façade of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Grand terrace of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Northern façade of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Grand terrace of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

External staircase of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Motor lobby entrance on the north façade of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

View towards the north on the lot of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Southern façade of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The guestrooms at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The lobby at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The Hotel Jaragua on its opening day: August 16, 1942 (Source: AGN)

-

The lobby at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The ballroom at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The Andalusian patio at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The rooftop garden at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The formal dining room at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The lobby at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The lobby at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Grand terrace of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The dining terrace at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

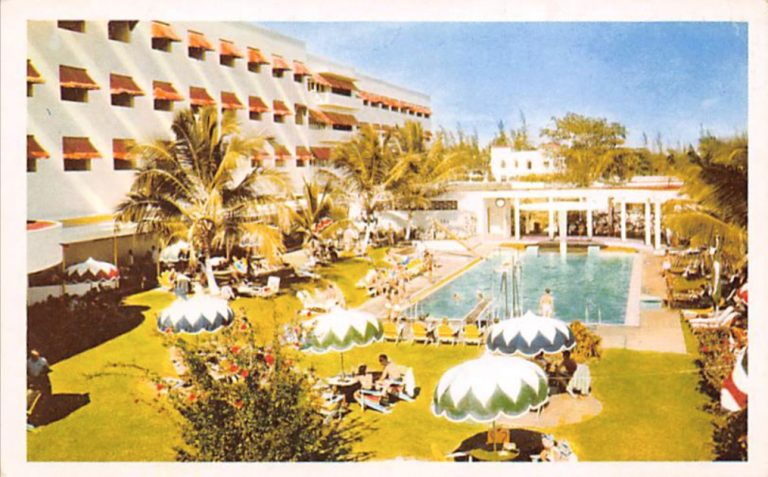

The pool area at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The pool area at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The bar area of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The kitchen area of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The kitchen area of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Southern façade of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

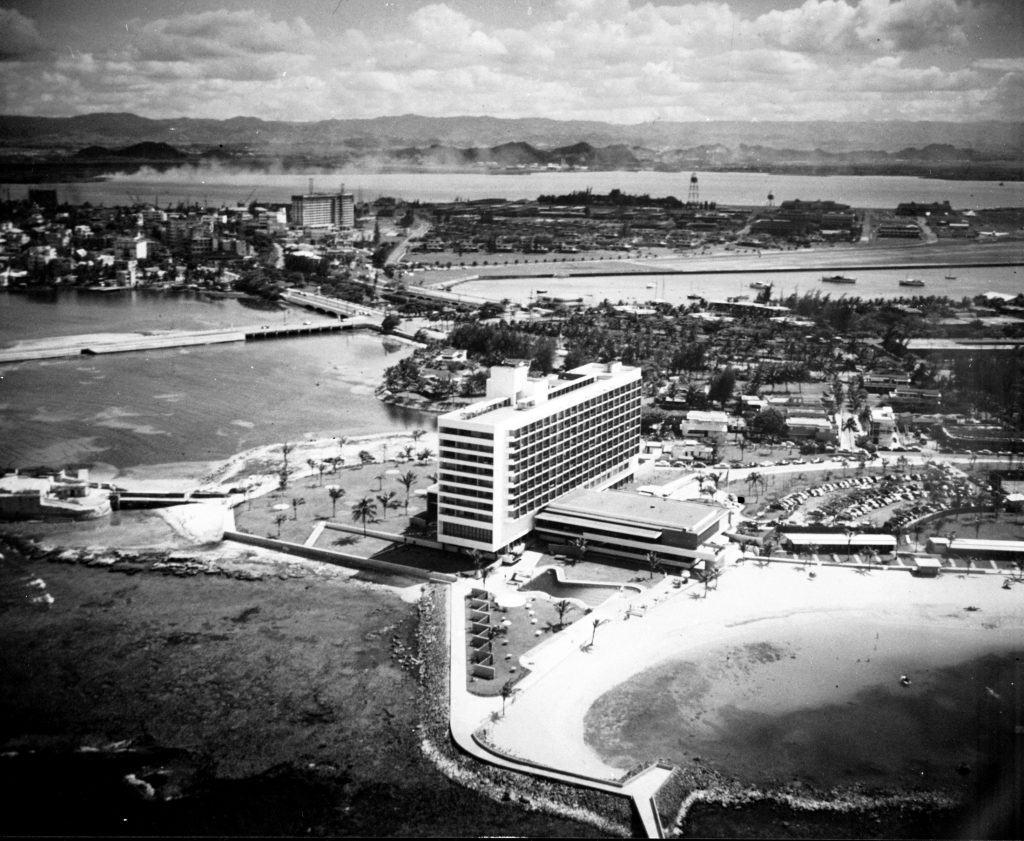

An aerial view of the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Despradel Catrain Family Archives)

-

An aerial view del Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

A couple of loans from here and there

-

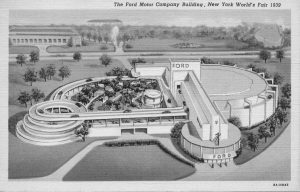

The Ford Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair (Source: Henry Ford Foundation)

-

A postcard of the Ford Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

Georges-Henri Pingusson's 1932 Hotel Latitude 43 in Saint-Tropez, France (Source: CNAM/SIAF. Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle)

-

Georges-Henri Pingusson's 1932 Hotel Latitude 43 in Saint-Tropez, France (Source: CNAM/SIAF. Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle)

-

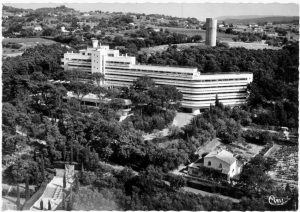

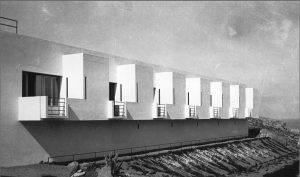

André Lurçat's 1929 Hotel Nord-Sud in Corsica, France (Source: CNAM/SIAF. Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle)

-

André Lurçat's 1929 Hotel Nord-Sud in Corsica, France (Source: CNAM/SIAF. Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle)

-

André Lurçat's 1929 Hotel Nord-Sud in Corsica, France (Source: CNAM/SIAF. Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture du XXe siècle)

-

Pauli and Märta Blomstedt's Pohjanhovi Hotel in Rovaniemi, Finland (Source: Finna Archive of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture)

-

Pauli and Märta Blomstedt's Pohjanhovi Hotel in Rovaniemi, Finland (Source: Finna Archive of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture)

-

Alvar Aalto's Maalaistentalo building in Turku, Finland, built between 1927-1928 (Source: Finna Archive of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture)

-

Alvar Aalto's Maalaistentalo building in Turku, Finland, built between 1927-1928 (Source: Finna Archive of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture)

-

Alvar Aalto's Viipuri Library, built in Russia between 1927-1935 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

-

Alvar Aalto's Viipuri Library, built in Russia between 1927-1935 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

-

Zeev Rechter's 1934 Hotel Kalia, built across the Dead Sea (Source: Rechter Architects)

-

Zeev Rechter's 1934 Hotel Kalia, built across the Dead Sea (Source: Rechter Architects)

-

Zeev Rechter's 1934 Hotel Kalia, built across the Dead Sea (Source: Rechter Architects)

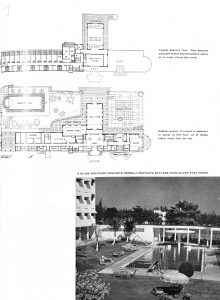

THE ORIGIN

But do note that the Jaragua was not wholly born in the Dominican Republic. The first to place rationalist hotels across the sea were the French: André Lurçat designed the Nord-Sud in Corsica (1929) and Georges-Henri Pingusson created Saint-Tropez's Latitude 43 (1932). One can ascertain the reference just by looking at those white volumes, with their glass surfaces facing a body of water.

There's also the matter of the Nordic countries. The Maalaistentalo Building (1927-1928) and the Viipuri Library (1927-1935), both by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, feature a series of openings that slightly resemble the choices made in the Jaragua project. The same can be said about the Pohjanhovi, a hotel designed by Pauli and Märta Blomsted in 1936: its composition is quite similar go its Caribbean counterpart.

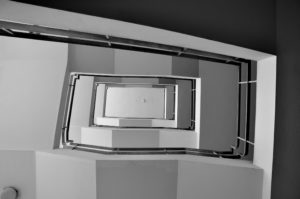

But no other element was the object of a copy+paste move as much as the hotel's exterior staircase: when González attended the 1939 New York World's Fair, he brought back as a souvenir the memory of the stairs at the Ford Motor Company pavilion, with its notorious curves swirling around a flagpole.

A master's approval

THE ASSESSMENT

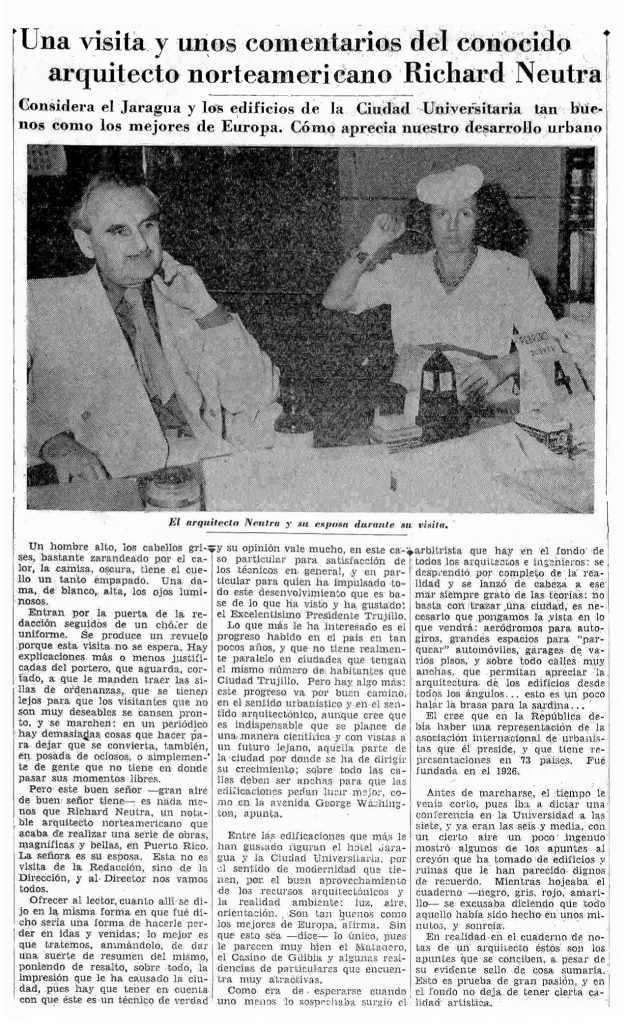

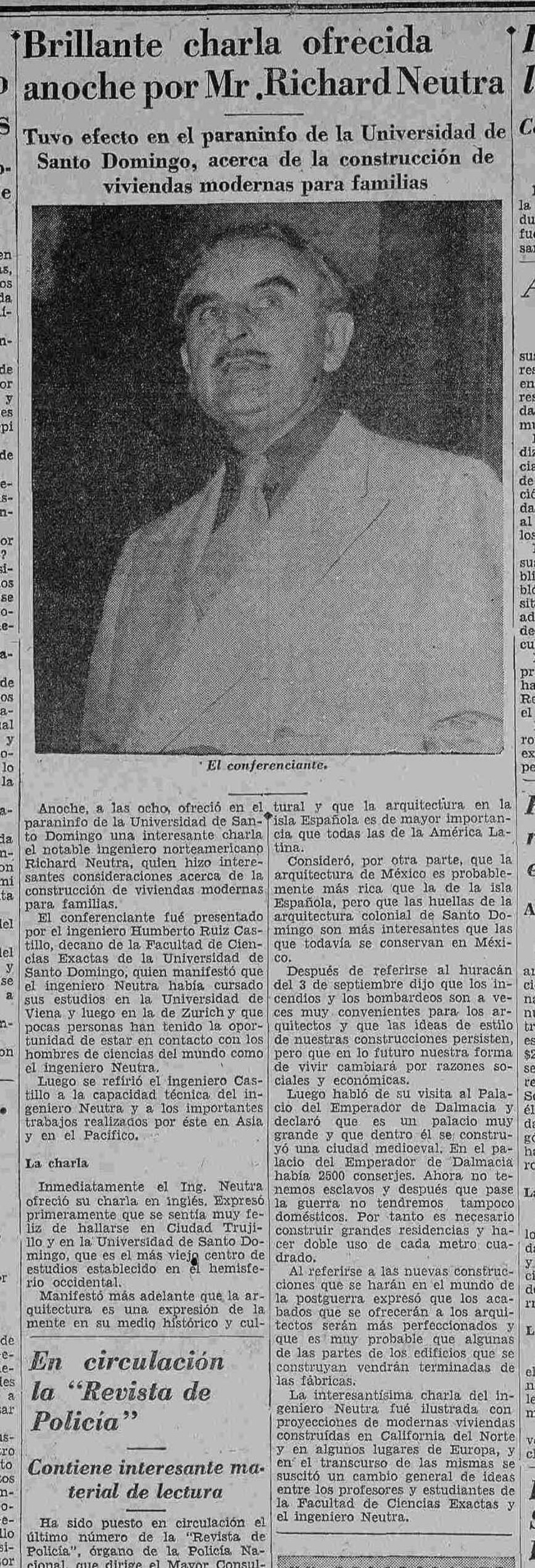

There was someone in particular who knew just how difficult it was to adapt rationalism to extremely sunny conditions: Richard Neutra, an Austrian-American architect who worked under the likes of Adolf Loos and Frank Lloyd Wright. The modernist style he developed in Southern California became so popular it is now inseparable from the area. Neutra visited Santo Domingo in March of 1945, on a short trip after spending some time working in Puerto Rico. Obviously, he stayed in the capital's best hotel, and during a conference at the University of Santo Domingo he didn't hesitate to state that Guillermo González's work was as good as the best rationalist buildings in Europe.

-

A March 7, 1945 clipping from La Nación (Source: AGN)

The most global of Dominican hotels

-

A review published in the September 1946 edition of American magazine Architectural Forum (Source: Architectural Forum)

-

A review published in the September 1946 edition of American magazine Architectural Forum (Source: Architectural Forum)

-

A review published in the September 1946 edition of American magazine Architectural Forum (Source: Architectural Forum)

-

Articles reproduced by Arquivox magazine in its 3-4 issue, dated 1985 (Source: Omar Rancier Archives)

-

Articles reproduced by Arquivox magazine in its 3-4 issue, dated 1985 (Source: Omar Rancier Archives)

-

Articles reproduced by Arquivox magazine in its 3-4 issue, dated 1985 (Source: Omar Rancier Archives)

-

Articles reproduced by Arquivox magazine in its 3-4 issue, dated 1985 (Source: Omar Rancier Archives)

-

THE PRESS

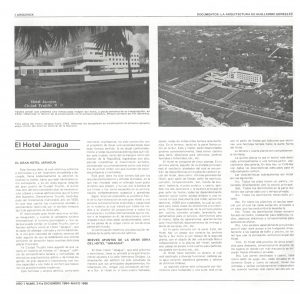

No other Dominican project had yet made it as far as the Jaragua Hotel: it was widely showcased in international architecture publications, even in spite of the troubled general climate due to World War II. For example, Interiors highlighted its design in 1944, while Proyectos y Materials and The Architectural Forum followed suit in 1945. The latter, in fact, dedicated a generous spread featuring the hotel's blueprints, as well as its long list of materials and suppliers.

Jaragua's trail in the Caribbean

THE IMPACT

Jaragua was the first hotel in the region to carry the torch of rationalism; that explains why its trail is quite visible in several neighboring countries. From the monumental Caribe Hilton in San Juan (1949), the Hotel del Lago in Maracaibo (1950) and the Hotel El Panamá (1946-1951) to Havana's Hotel Riviera (1957) and San Juan's Hotel La Concha (1959). The Lesser Antilles were also under its aesthetic influence, as evidenced by Saint Thomas' Virgin Isle Hotel (1951) and the Aruba Caribbean Hotel (1959). Although these proposals did surpass the Jaragua Hotel in scale, amenities and programming, its pioneering role is undeniable... although, to date, it has been unjustly ignored as a precursor with a strong influence on the region's hotel design.

-

Osvaldo Toro, Miguel Ferrer and Luis Torregosa's 1949 Caribe Hilton Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico (Source: Architecture and Construction Archive of the University of Puerto Rico)

-

Holabird, Root & Burgee's 1953 Hotel del Lago in Maracaibo, Venezuela (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

Edward Durell Stone, Octavio Méndez Guardia and Harold Sander's Hotel El Panamá, built between 1946-1951 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

The 1951 Virgin Isle Hotel in Saint Thomas (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

Morris Lapidus's 1959 Aruba Caribbean Hotel (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

The place to see and be seen, both night and day

THE NIGHTLIFE

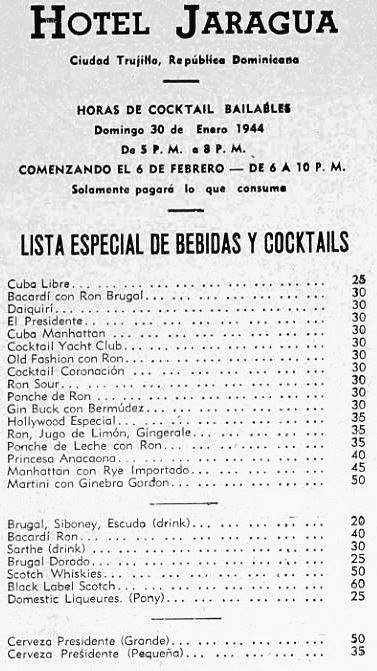

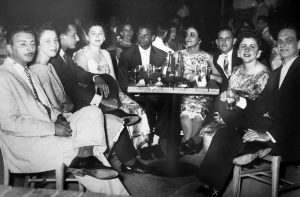

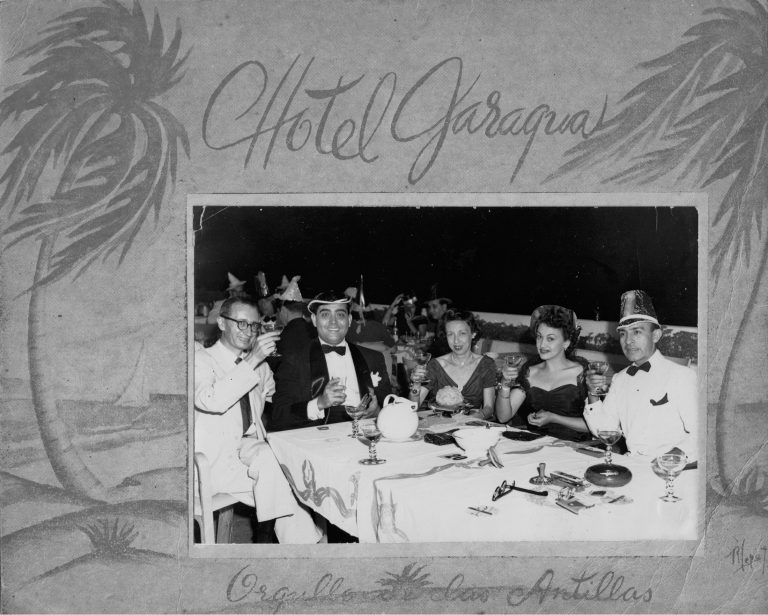

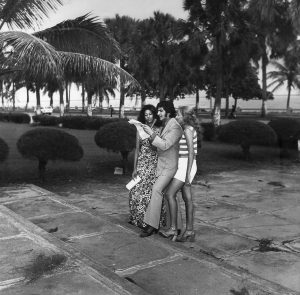

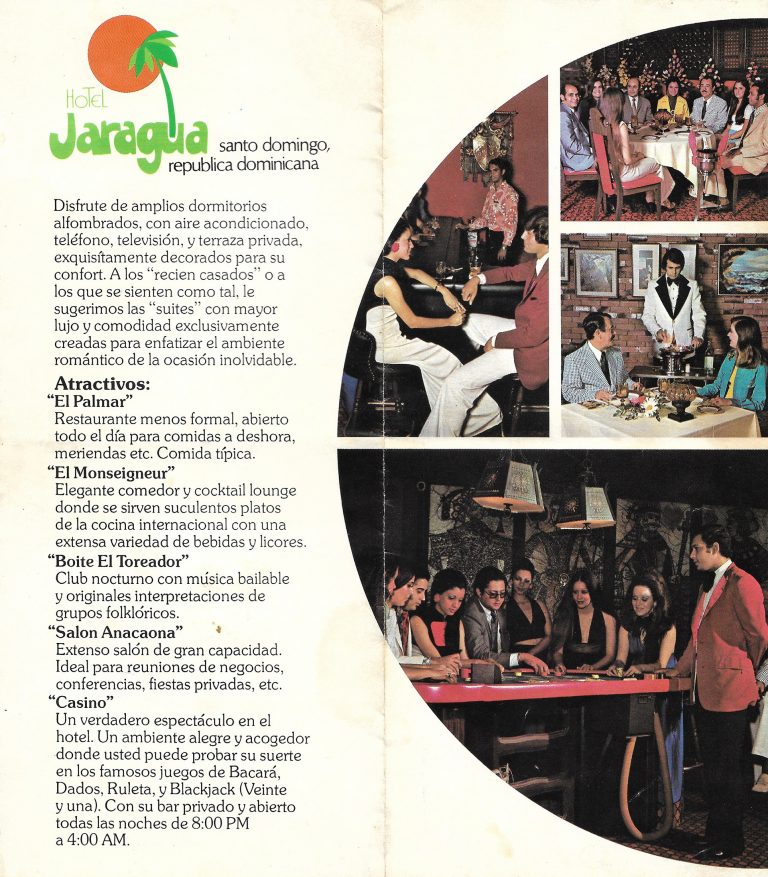

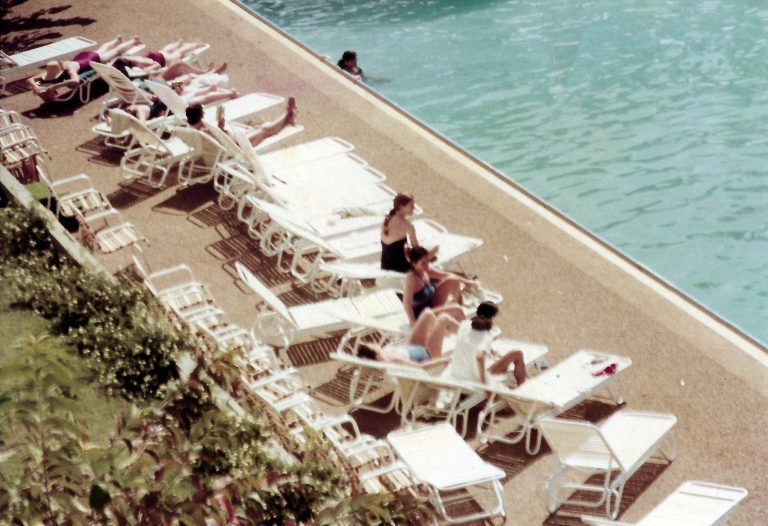

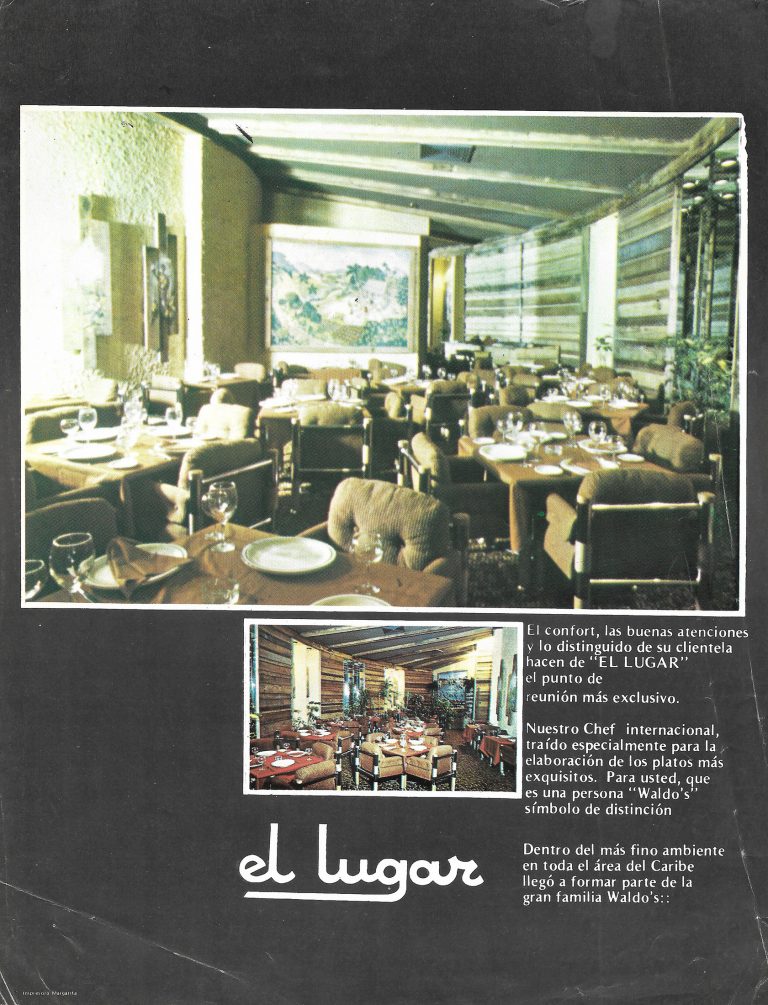

Up until the mid 50s the hotel was, without a doubt, the epicenter of Ciudad Trujillo's social life for the capital's crème de la crème. By day the it spot was the pool, where visitors would sunbathe and share the garden and the sea views. By sundown, the large terrace was the stage for many dances under the moon. The hotel's event calendar seemed endless: from fashion shows to live music to government celebration, Dominican-themed nights and private parties. The schedule was full of musical reviews, as well as a bevvy of entertainment spaces to choose from: it had a casino, a bar and a restaurant, with the latter featuring both local and international cuisine.

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Angelita Trujillo, the queen of the White Ball of San Andrés held in 1954 at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

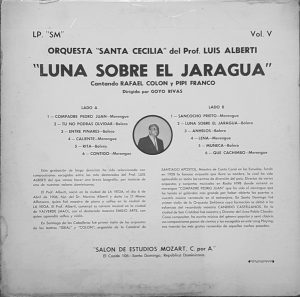

A hotel with its own soundtrack

-

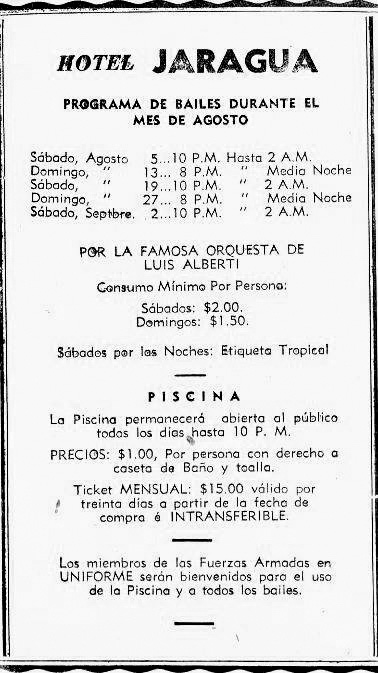

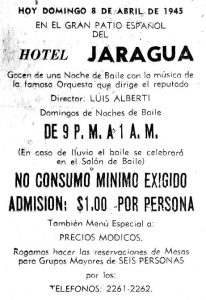

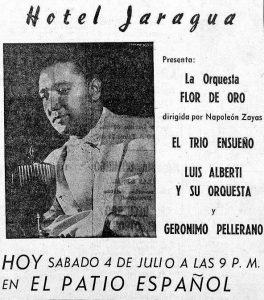

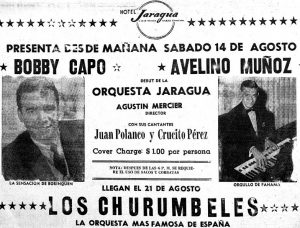

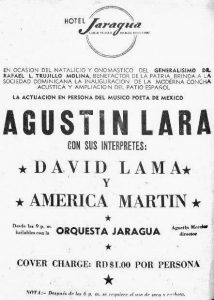

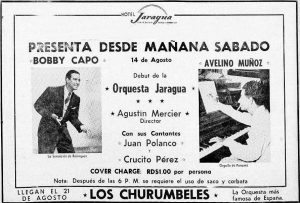

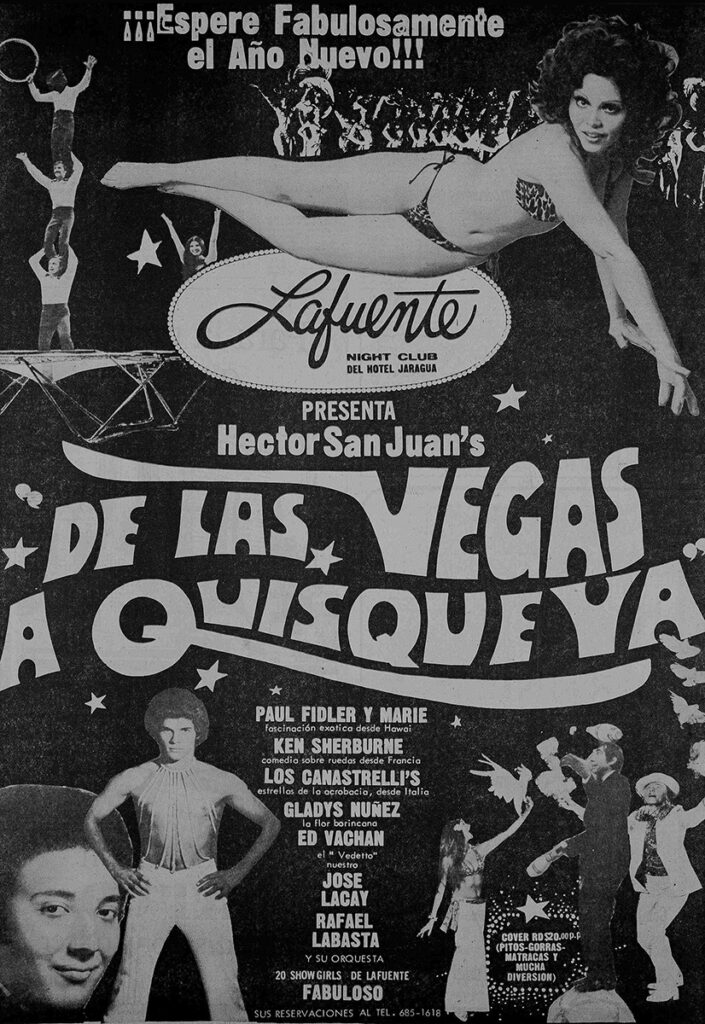

A poster of social events held at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

Luis Alberti's band (Source: AGN)

-

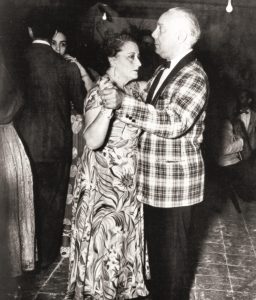

Guests and celebrities dancing at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities dancing at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

Guests and celebrities mingling in the hotel (Source: AGN)

-

María Martínez de Trujillo and Rafael L. Trujillo dancing (Source: AGN)

-

A poster of social events held at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

The Santa Cecilia Band (Source: AGN)

-

A poster of social events held at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

A poster of social events held at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

A poster of social events held at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

A poster of social events held at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

Medley from the midnight set at the Jaragua Hotel

Generalísimo Trujillo Band, led by Luis Alberti

Live recording by Fabio Herrera in the 1950s

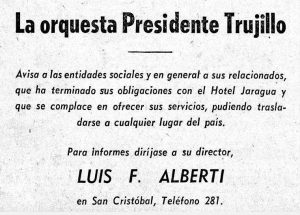

THE MUSIC

Just the sheer name "Jaragua" became shorthand for live music: in the 40s and 50s José Manuel López's band would play from Monday through Friday, while the weekends belong to Luis Alberti, the leader of the Orquesta Generalísimo Trujillo. The band had a repertoire that included Toda una vida and Quizás, by Osvaldo Farrés; Bésame mucho by Consuelo Velásquez and Capullo de alelí by Rafael Hernández. The bolero section usually featured Paraíso soñado and Ven, both by Manuel Sánchez Acosta, as well as Apasionado by Águeda Blandino, No te vayas by Luis Chabebe and Concierto de amor by Nicolás Yabra; the merengue spotlight featured the likes of El sancocho prieto, Loreta and Caliente, written by Alberti himself.

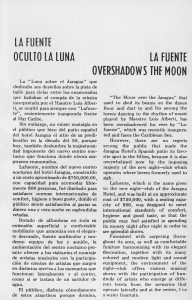

The moon does have its favorite spot over the Dominican Republic

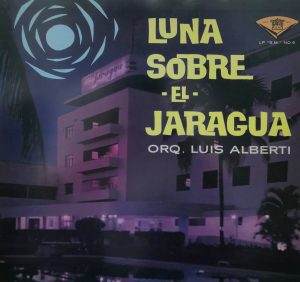

THE MOON

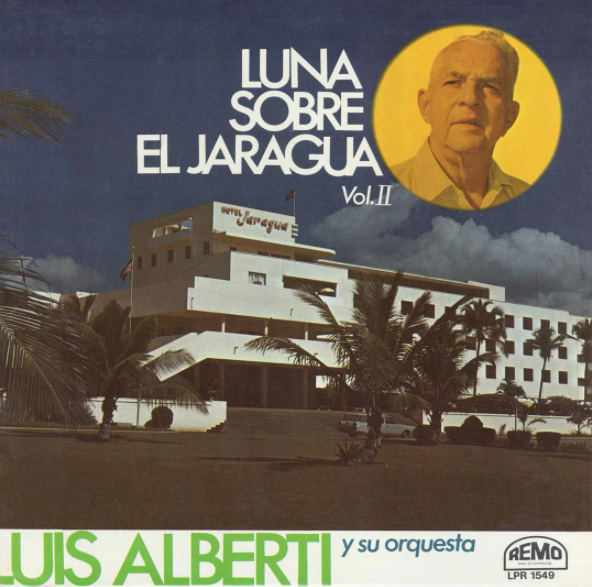

How many hotels can brag about having their own theme song? Party nights at the Jaragua had a high point, a particular moment that quickly became tradition: Luna sobre el Jaragua. At midnight, the voice of the so-called Ebony Spike, Rafael Colón, would sing the lyrics of a song penned by Alberti that became the hotel's official song.

The moon over the Jaragua

Throws a jealous look

At such magnificence

The moon over the Jaragua

Would love to dress us up

With silver and love

The outline of the palm trees

The murmur of the sea

And dreamy embraces

Can be heard all around

-

The Generalísimo Band, led by Luis Alberti, performing at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: AGN)

-

The cover of Luis Alberti's Luna sobre el Jaragua LP album (Source: Salón Estudios Mozart)

-

The back cover for Luis Alberti's Luna sobre el Jaragua LP album (Source: Salón Estudios Mozart)

-

Luis Alberti's Luna sobre el Jaragua album (Source: Salón Estudios Mozart)

-

Luna sobre el Jaragua, a song written by Luis Alberti, performed by Rafael Colón

1951

Record company: Salón Mozart

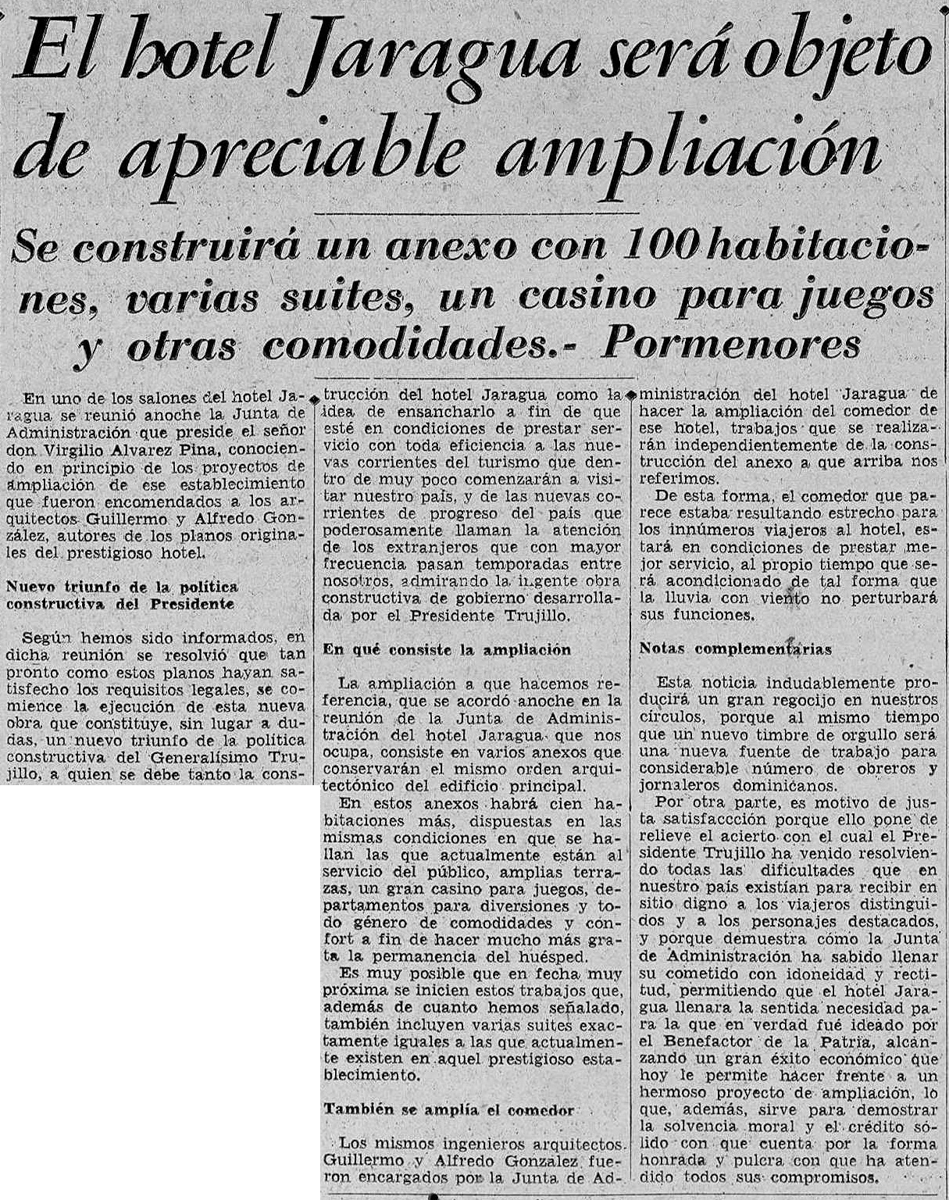

A set of expansions the size of Trujillo's ego

-

A wing of guestrooms in an eastern-facing addition, as well as the new bungalows towards the south (Source: AGN)

-

The bungalows at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Despradel Catrain Family Archives)

-

The bungalows at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Despradel Catrain Family Archives)

-

The dining room's expansion in 1946 (Source: AGN)

-

Some poolside lounging at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

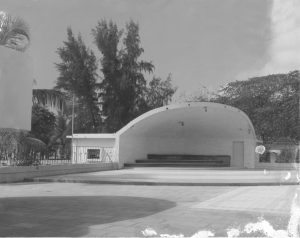

The concrete bandstand, placed southwest of the Spanish courtyard, was built in the 1950s (Source: AGN)

-

The concrete bandstand, placed southwest of the Spanish courtyard, was built in the 1950s (Source: AGN)

-

Some poolside lounging at the Hotel Jaragua (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez Archives)

-

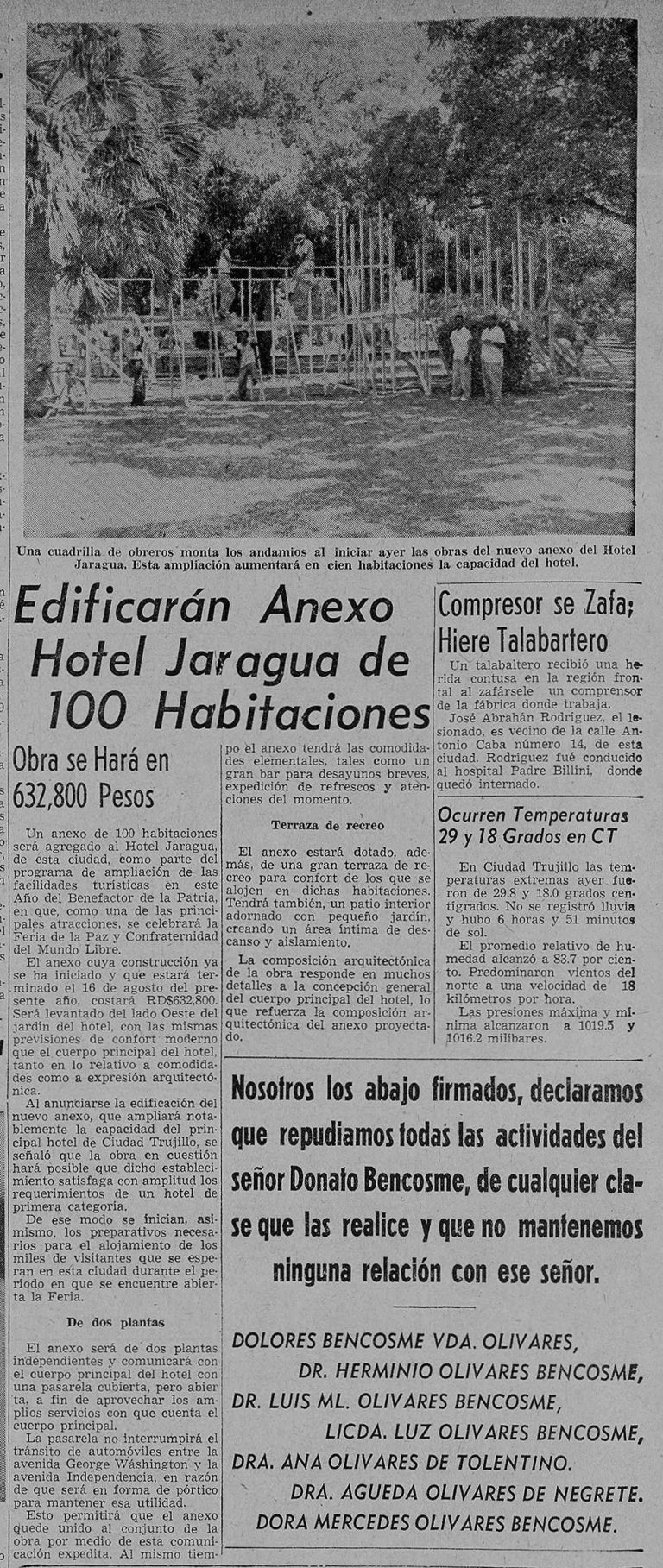

A February 5, 1955 clipping from El Caribe (Source: AGN)

-

The northern standalone annex of Hotel Jaragua was built for the 1955 Fair for Peace and Fraternity (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The northern standalone annex of Hotel Jaragua was built for the 1955 Fair for Peace and Fraternity (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The northern standalone annex of Hotel Jaragua was built for the 1955 Fair for Peace and Fraternity (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Anerial view of the Hotel Jaragua in 1960 (Source: Max Pou - Centro León)

-

An aerial view of the Hotel Jaragua in 1960 (Source: Max Pou - Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

-

THE EXPANSION

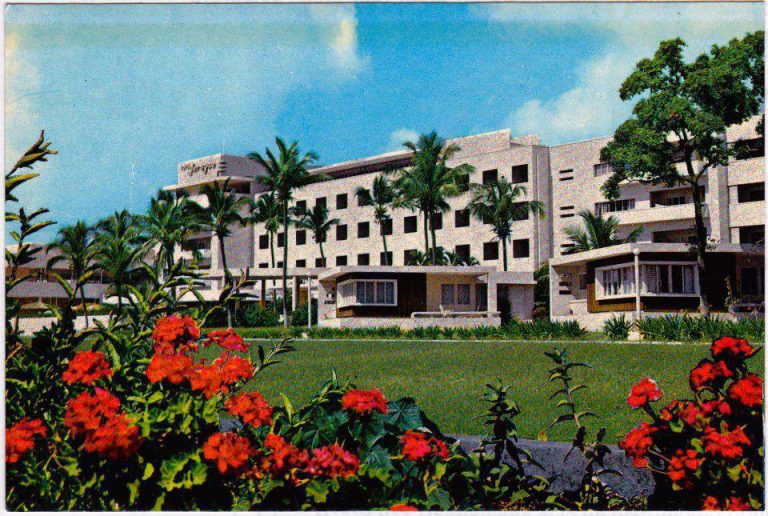

In spite of Trujillo's negative reputation, which kept many would-be visitors away, his machinery kept believing in the idea of a large-scale tourism industry for Santo Domingo. That explains why, in 1948, the González siblings received a commission for an expansion; they built five detached bungalows and 57-guestroom annex towards the east. The casino was moved to a new spot on the second floor and the main dining room grew to an even grander scale. // In the 50s, the southern façade got its brick-red awnings, the rooftop garden had its trellis and the grand terrace got a new bandstand. Nevertheless, no expansion at the time was as noticeable as the project undertaken for the preparations of the Fair for Peace and Fraternity in the Free World, an event brought along by Trujillo's desire to show the world the modern nation he had created. González was hired to increase the hotel's capacity with a 100-guestroom annex, located to the northwest side of the lot. This building, connected to the mothership via a walkway, was popularly known as the Holiday Inn, as it was then operated by the American hotel chain of the same name.

Far more supply than demand

THE OVERSUPPLY

Due to the 1955 fair, the city ended up with more guestrooms than guests due to the birth of three new hotels: the Paz, the Generalísimo and the Embajador —the latter was built following the era's luxury standards. These newcomers, located in a relatively close radius, would come to create an oversupply of hotel rooms and entertainment options that would make a dent on the (until then unbeatable) Jaragua. And that, precisely, marked the beginning of the end.

-

Santo Domingo's Hotel Embajador, designed in 1955 by Roy France (Source: Francis Stoppelman)

-

Santo Domingo's Hotel Embajador, designed in 1955 by Roy France (Source: Francis Stoppelman)

-

Santo Domingo's Hotel Embajador, designed in 1955 by Roy France (Source: AGN)

-

Santo Domingo's Hotel Generalísimo, later labeled Hotel Comercial, was designed by William Reid Cabral and José Manuel "Nani" Reyes in 1955 (Source: Lidia León Archives)

The Revolution is at the door

-

A group of tanks took over Santo Domingo's Malecón, near the Hotel Jaragua, during the 1965 Civil War (Source: Thimo Pimentel)

-

The hotel during the 1965 Civil War (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

The hotel during the 1965 Civil War (Source: Américo Mejía Archives)

-

The hotel during the 1965 Civil War (Source: Intervention in the Caribbean - The Dominican Crisis of 1965, by Bruce Palmer Jr.)

-

Shooting Incident in Santo Domingo 1965

Ted Yates' interview with Al Burt, broadcast on the NBC News Hotline, as he reported on the civil war and US intervention in the country

University of Florida Archive

THE INTERVENTION

Four years after Trujillo's assasination, in 1965 the country was in revolt, as civilians joined by the military took to the streets of Santo Domingo to try to reinstate Juan Bosch's constitutional government, overturned by a coup in 1963. Fighting intensified due to the intervention of the United States, with the troops of the so-called Interamerican Peace Force, created by the OAS. The Force rented the Jaragua Hotel's main building as lodging, and that stay sadly damaged its infrastructure, leaving it worse for wear.

In the red

-

The hotel was in a state of disarray in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel was in a state of disarray in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

An August 23, 1967 clipping from El Caribe (Source: AGN)

-

An August 23, 1967 clipping from El Caribe (Source: AGN)

-

THE HAVOC

While Trujillo's government did have a long-term vision for tourism development, the truth was that the Jaragua Hotel was not profitable. There weren't enough check-ins to cover the costs of maintenance, but while Trujillo was alive it became rather commonplace to alter the bottom line in order to keep the dictator's whims at bay.

What's more, the hotel went through an unfortunate series of rescinded contracts, since many companies promised to embark on a full revamp of the building and ended up running away due to the high costs involved. Between 1942 and 1973 management had gone through 12 different pairs of hands, both local and foreign companies. Thanks to such swings, it became normal to close a year in the red. This administrative instability led to having a building that was simply not in any condition to keep up with market demands.

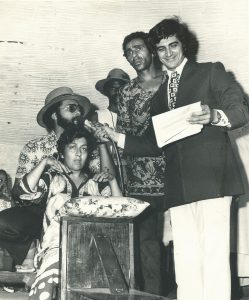

Live, from El Jaragua, it's...

THE MEDIA

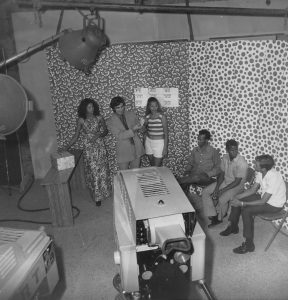

And yet, in the 60s and 70s the hotel was used rather creatively for activities that went beyond hospitality. In 1963 Ellis Pérez set up his radio station, Radio Universal, on the eastern side of the lot. The station became known as a pioneer for its live broadcasts of MLB games, and had its HQ in the hotel grounds until 1977.

But it wasn't just radio: on the second floor, to the west, were located the first Santo Domingo-based studios of Color Visión, as the Santiago de los Caballeros team moved the TV station to the capital in 1971. The hotel became the set for shows such as El sheriff Marcos and La casa de Pequitas on weekdays, while weekends featured the likes of Show de Shows and Domingo de mi ciudad —the latter hosted by Horacio Lamadrid using several of the hotel's public spaces.

-

Color Visión's studios, located inside the Hotel Jaragua, in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

-

An ad for Domingo de mi ciudad, a TV show produced by Horacio Lamadrid, filmed within the premises of the Hotel Jaragua in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

-

Behind the scenes of Domingo de mi ciudad, a TV show produced by Horacio Lamadrid and filmed within the premises of the Hotel Jaragua in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

-

Behind the scenes of Domingo de mi ciudad, a TV show produced by Horacio Lamadrid and filmed within the premises of the Hotel Jaragua in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

-

Behind the scenes of Domingo de mi ciudad, a TV show produced by Horacio Lamadrid and filmed within the premises of the Hotel Jaragua in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

-

Behind the scenes of Domingo de mi ciudad, a TV show produced by Horacio Lamadrid and filmed within the premises of the Hotel Jaragua in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

-

Behind the scenes of Domingo de mi ciudad, a TV show produced by Horacio Lamadrid and filmed within the premises of the Hotel Jaragua in the early 1970s (Source: Horacio Lamadrid Archives)

A swan song

-

An aerial view of the Hotel Jaragua in the late 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's pool area after the renovations carried out during the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's pool area after the renovations carried out during the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

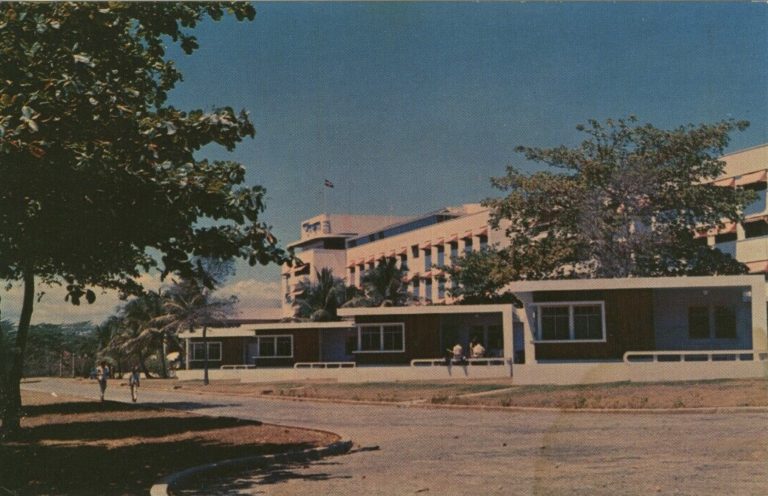

The hotel's northern façade after the renovations that took place in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's bar area after the renovations that took place in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's restaurant section after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's restaurant section after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Papito Santa Cruz (center) in his office, surrounded by Héctor De San Juan, Ramón Pérez and César Suárez (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's casino area after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's casino area after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's casino area after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's casino area after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

The hotel's casino area after the renovations carried out in the early 1970s (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

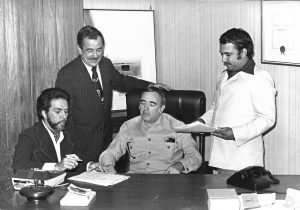

THE REBIRTH

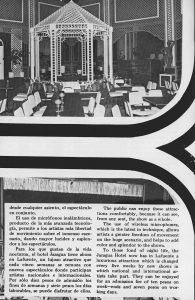

By the early 70s, the Jaragua Hotel had still failed to become profitable; it urgently needed someone who could see the operation under a different light. Fortunately, someone was willing to give it a chance: José Hernández Santa Cruz, known as Papito Santa Cruz, a Cuban businessman with previous experience in casinos, restaurants and night clubs both in the Dominican Republic and overseas. Although Santa Cruz had never been at the helm of a hotel, he rose to the challenge of a head-to-toe revamp valued at 1.2 million pesos, as the building was in a dire state. The process went from the ceiling to the AC units to the common areas and a full set of new furniture, as well as the façades, the pool area, old restaurants brought back to life and a new two-story casino. But there was one project in particular that would stand out in the middle of it all: La Fuente.

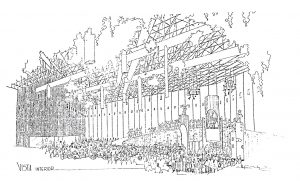

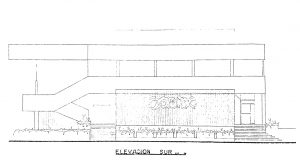

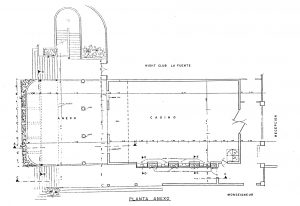

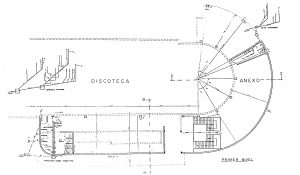

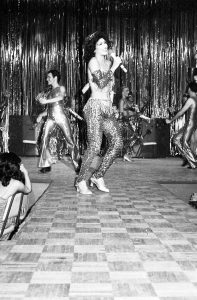

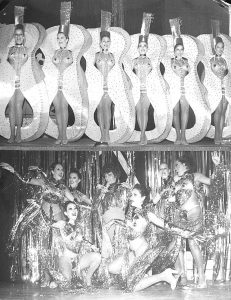

Vegas-style entertainment

THE SHOW

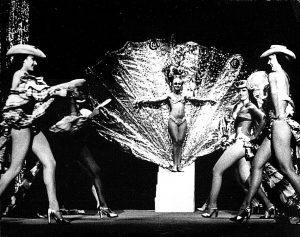

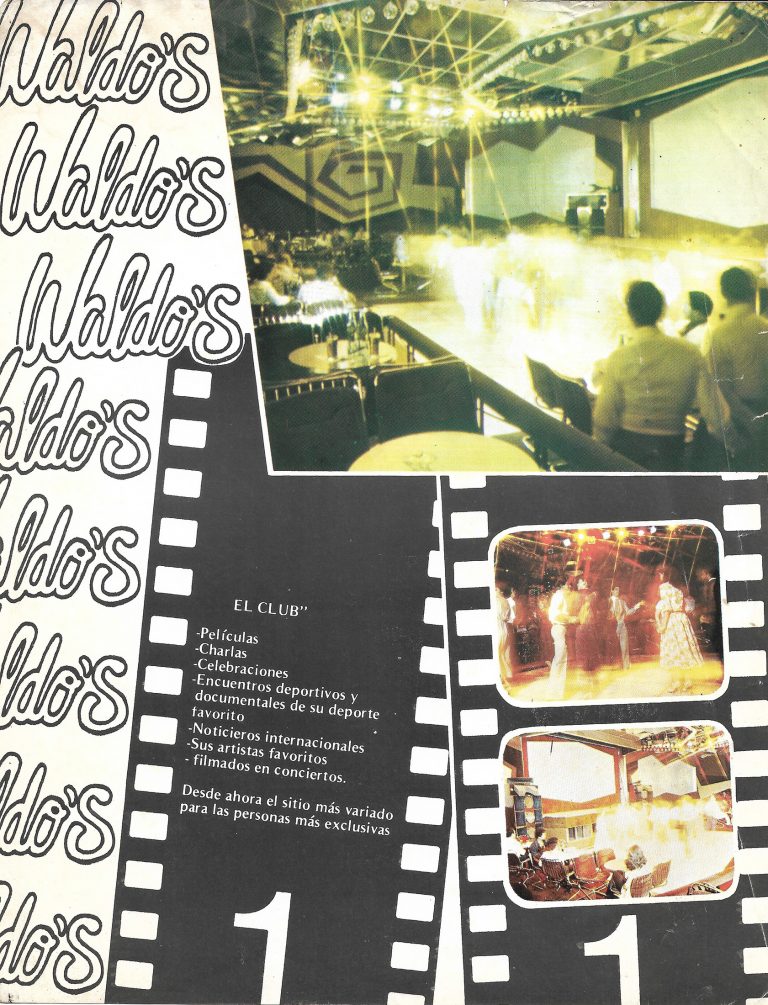

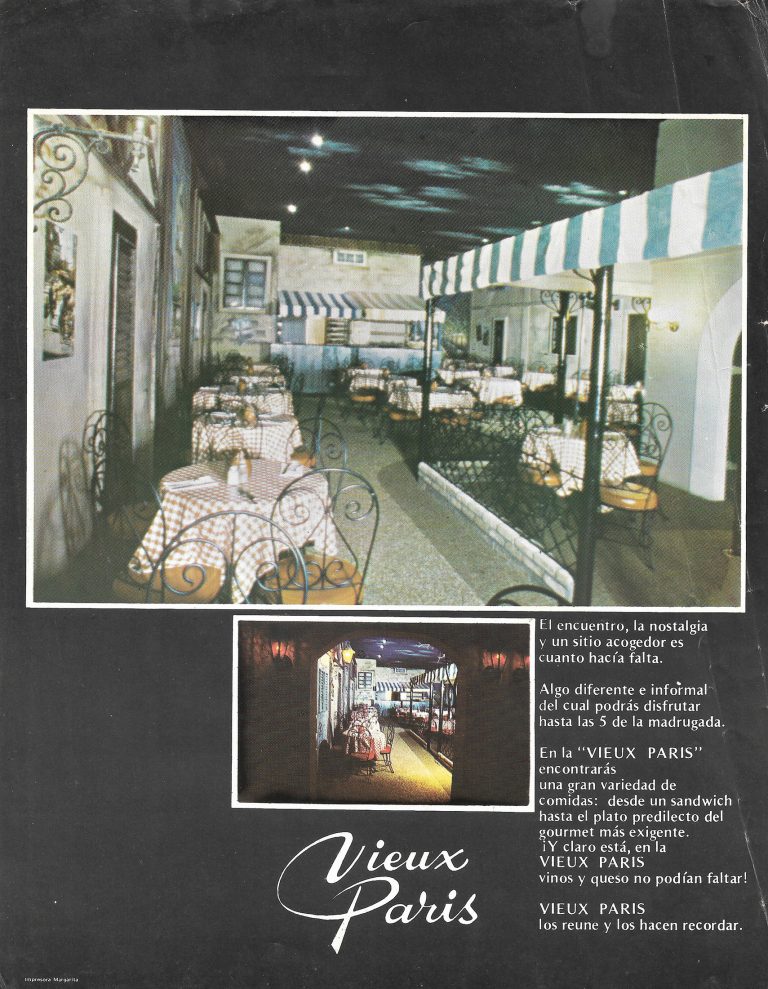

Opened in December of 1975 with a budget of 750 thousand pesos, the event hall known as La Fuente replaced the hotel's former grand terrace, turning it into an indoors space headed by a large floating metallic structure. In his proposal, architect Manuel Del Orbe saw to it that Guillermo González's original proposal would be as protected as possible, so he used distinctive materials to separate the new from the old. In its terraced interior, with an 800-seat capacity, stood the country's first hydraulic stage, and it was decorated with finishings and objects imported from Miami. Apart from the in-house band led by Rafael Labasta, La Fuente had a Vegas-style show full of local and foreign dancers, as well as starring figures like José Lacay and Ed Vachan, popularly known as El Vedetto. That hydraulic stage would in turn host a bevvy of international artists, including Camilo Sesto, Marco Antonio Muñiz, Danny Rivera, Donna Summer and Barry White.

-

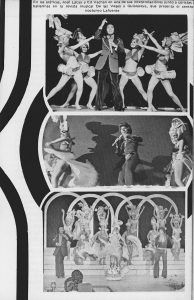

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

La Fuente and the hotel's exterior staircase (Source: Omar Rancier Archives)

-

Exterior view of La Fuente (Source: Lidia León Archives)

-

Exterior view of the annex to the hotel's casino (Source: Lidia León)

-

Exterior view of the rear annex of the hotel (Source: Lidia León)

-

Exterior rendering for La Fuente, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

Interior rendering for La Fuente, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

La Fuente's floor plan, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

La Fuente's southern façade, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The casino annex floor plan, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The rear annex floor plan, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The rear annex floor plan, designed by Manuel Del Orbe in 1975 (Source: Lidia León)

-

An ad announcing the opening of La Fuente in 1975 (Source: AGN)

-

A 1975 ad announcing the many activities taking place at La Fuente (Source: AGN)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

-

An article on La Fuente's opening (Source: Bohío Magazine)

-

An article on La Fuente's opening (Source: Bohío Magazine)

-

An article on La Fuente's opening (Source: Bohío Magazine)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

-

Some Vegas-style shows at La Fuente (Source: Santa Cruz Family Archives)

Stop the partying

THE IMPASSE

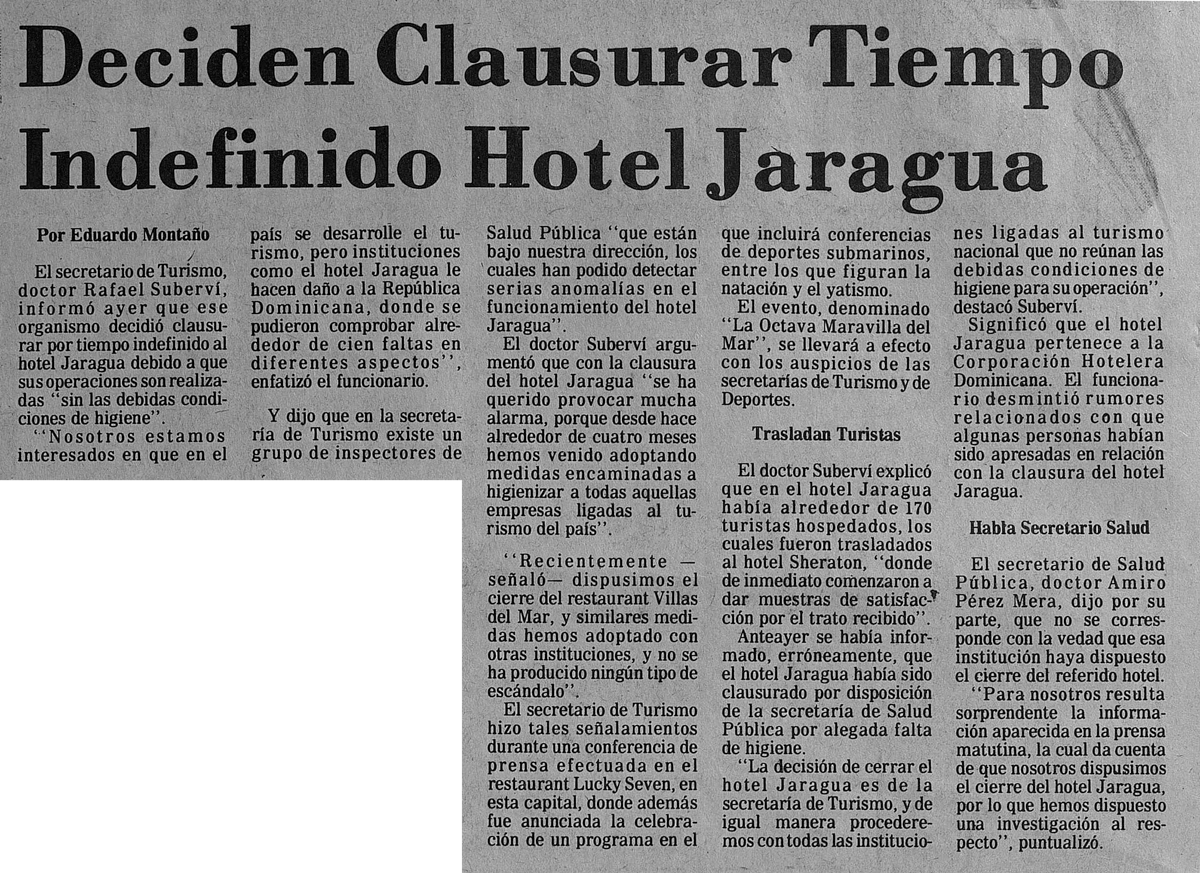

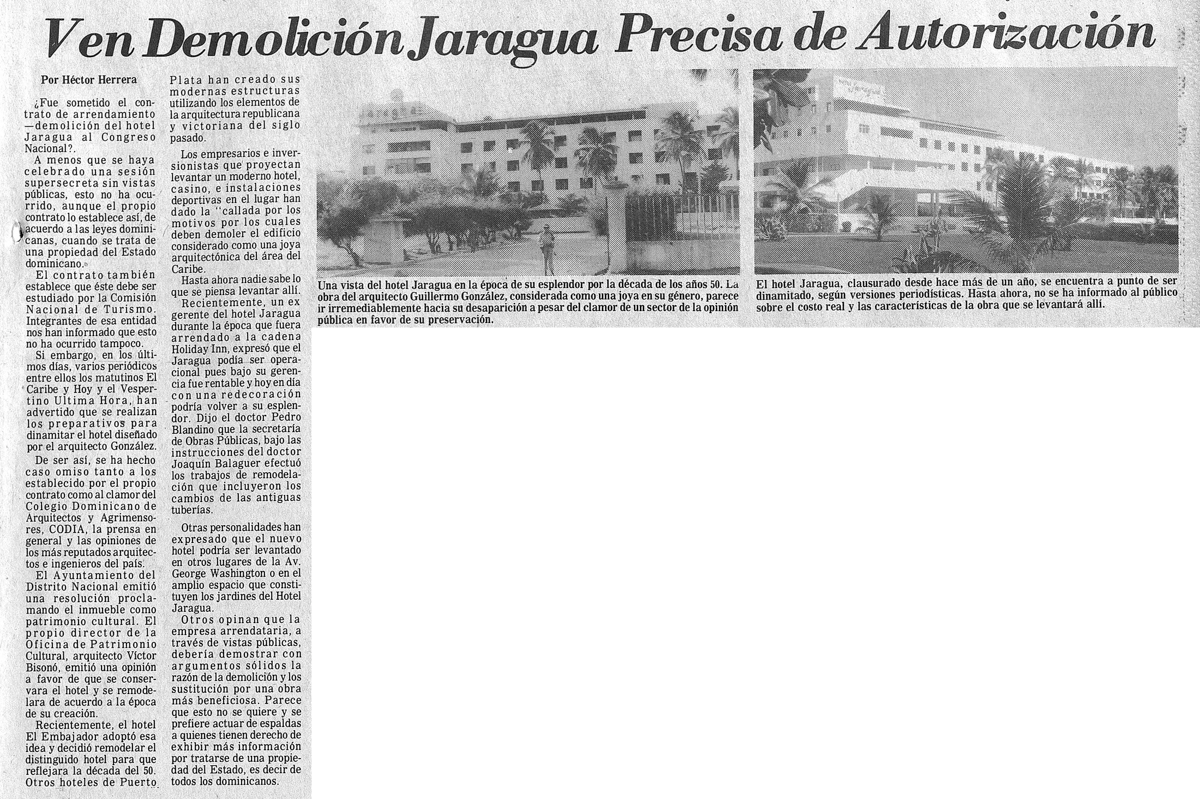

Business was booming, and so in 1976 Papito Santa Cruz signed a contract with the government that extended the original 1973 document for 20 more years. Nevertheless, as there was a new incoming administration in 1982 with the arrival of President Salvador Jorge Blanco, things would change. In the final days of that year and in the middle of his successful management streak, the Secretary for Tourism shut down the Jaragua Hotel due to a purported lack of hygiene. Santa Cruz and his family were forcibly evacuated from the premises, and the establishment was closed down even as tourists were still checked in.

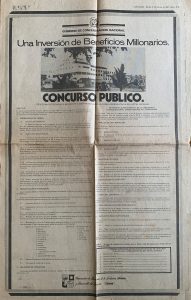

And then, in April of 1983 the government announced the winners of a public call for proposals for a new lease. There was no clear winner here, due to the intervention of Jorge Blanco's leanings towards people in his own circle, but finally in 1984 a new winner was announced: the Compañía Transamerican Hotel y Casino S.A. had signed a 30-year contract. And meanwhile the hotel, shut down since December of 1982, fell in a state of disarray.

-

A December 23, 1982 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

-

A public announcement published in Listín Diario on February 22, 1983 (Source: AGN)

-

A June 30, 1984 clipping from El Caribe (Source: AGN)

-

The hotel was shut down by the military prior to its demolition in 1985 (Source: AGN)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel was shut down in 1984 (Source: Lidia León)

Fighting against an impending end

-

An August 14, 1984 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

-

An August 8, 1984 article from El Nuevo Diario (Source: AGN)

-

A September 13, 1984 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

-

A September 19, 1984 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

-

A September 30, 1984 clipping from El Nacional (Source: AGN)

-

A November 7, 1984 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A November 7, 1984 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A November 11, 1984 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A February 14, 1985 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A February 14, 1985 clipping from El Nacional (Source: AGN)

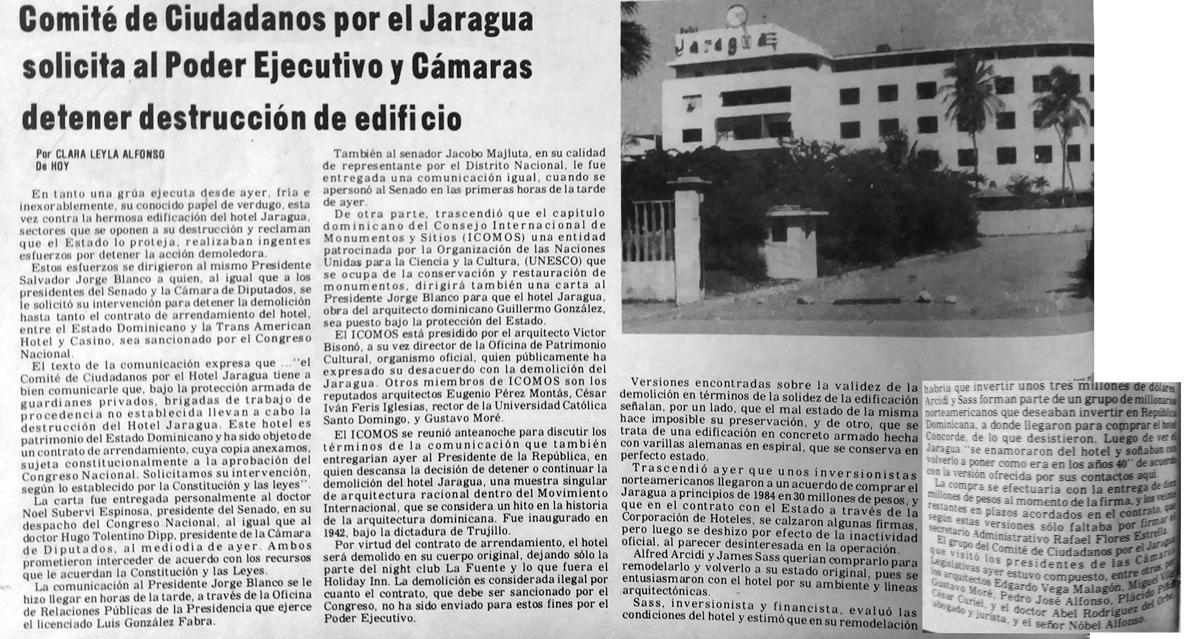

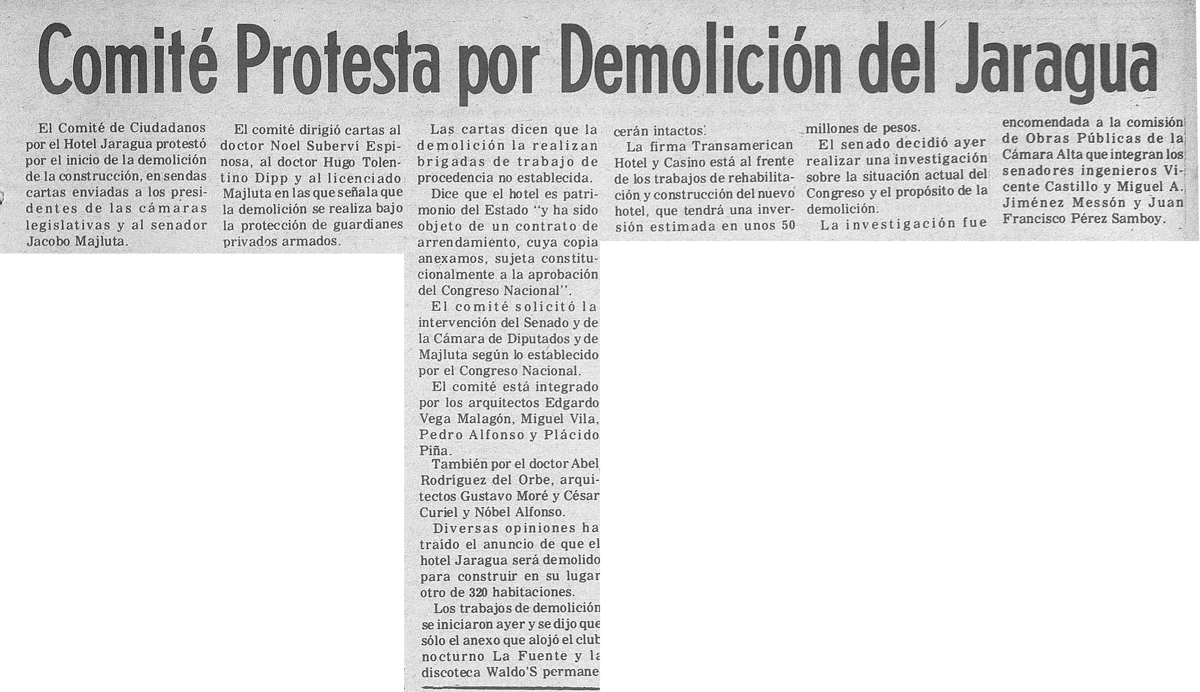

THE THREAT

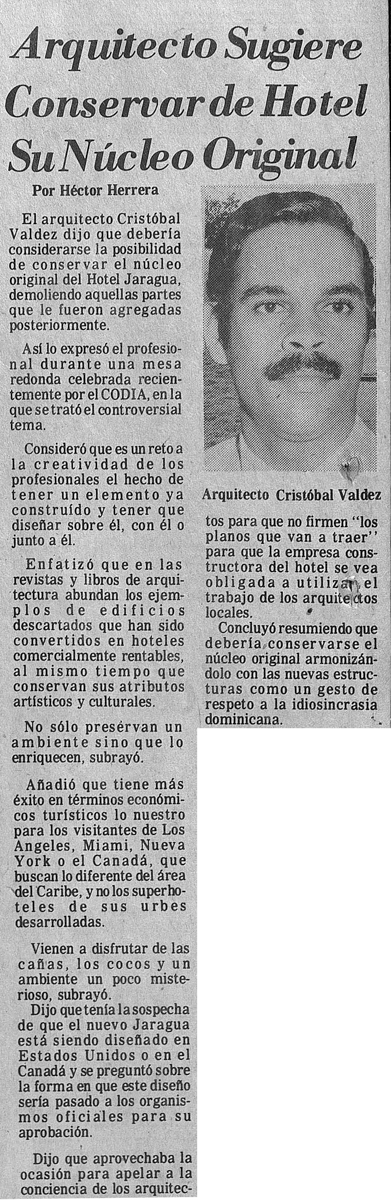

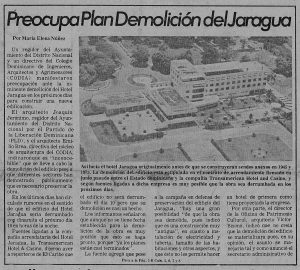

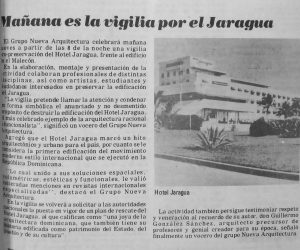

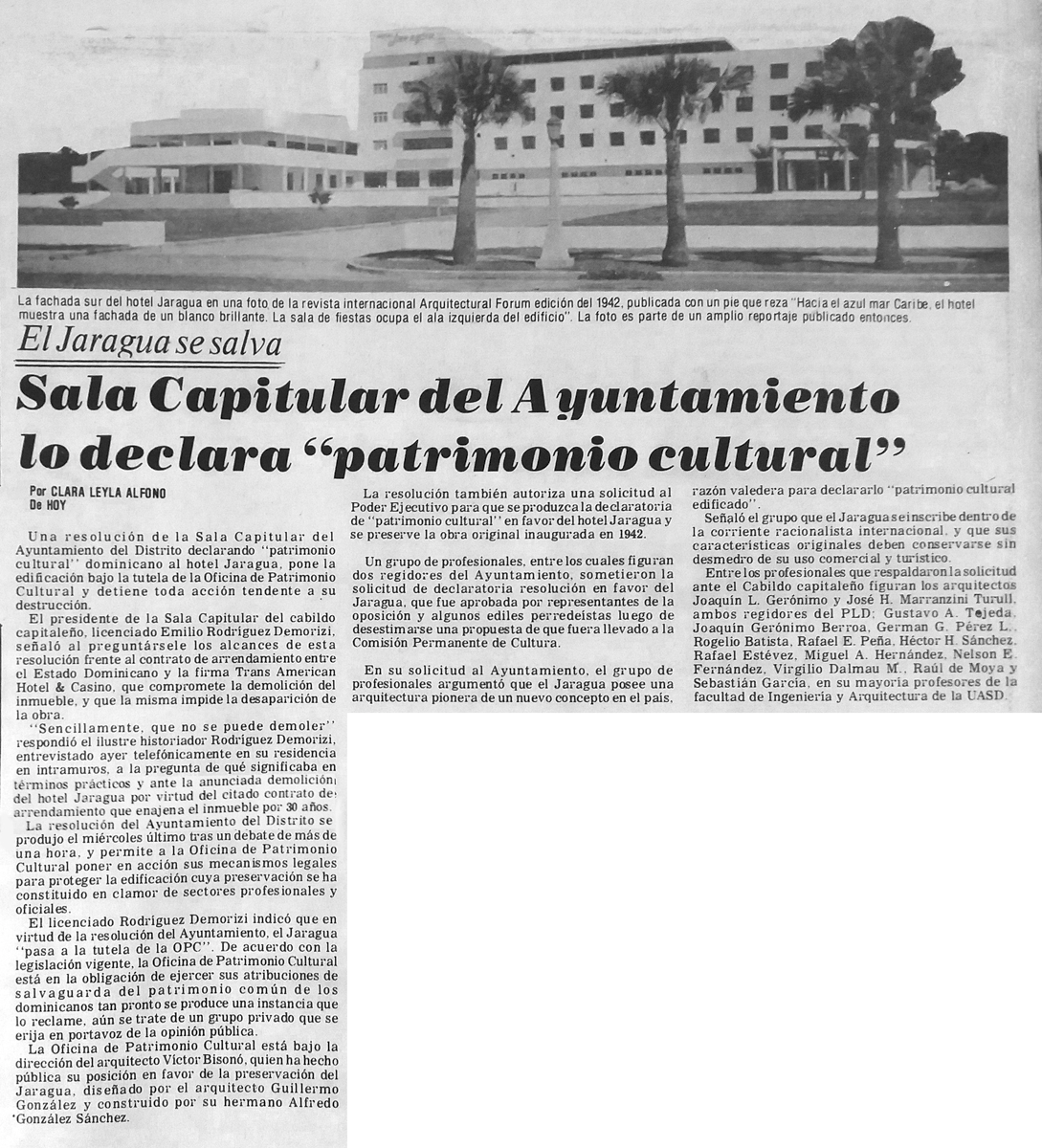

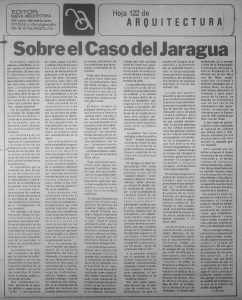

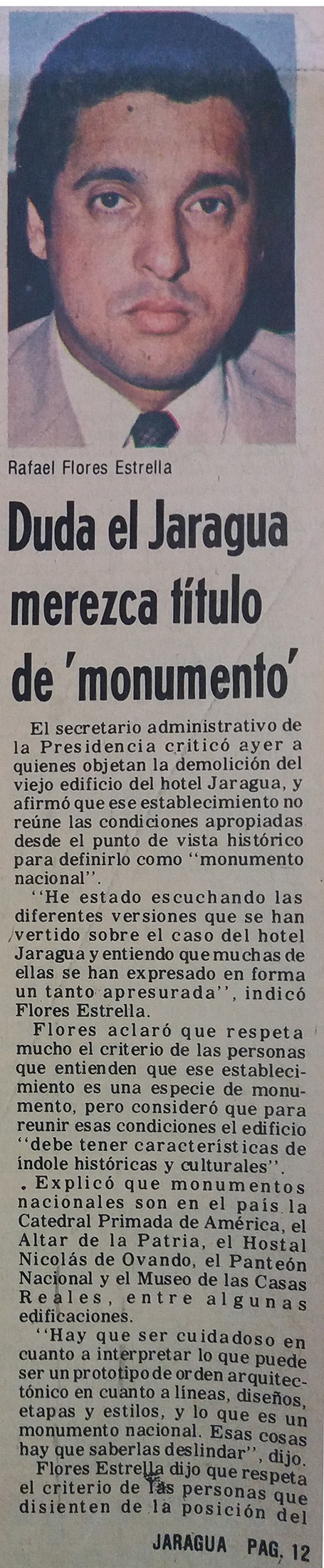

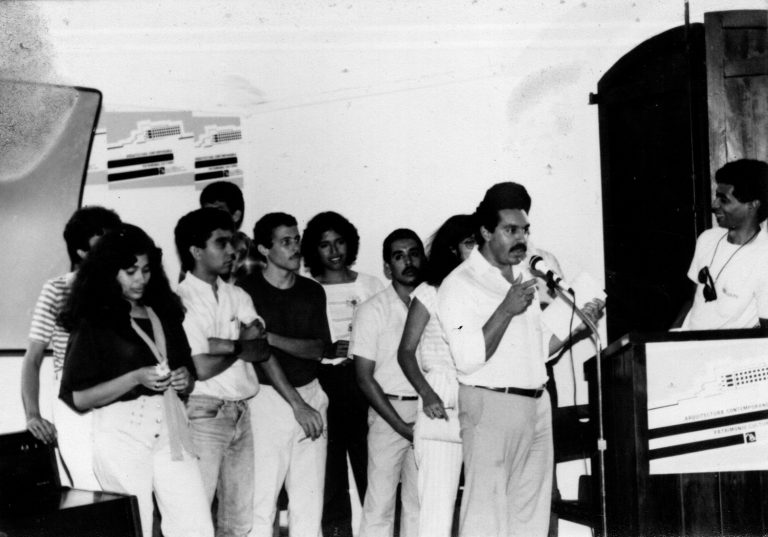

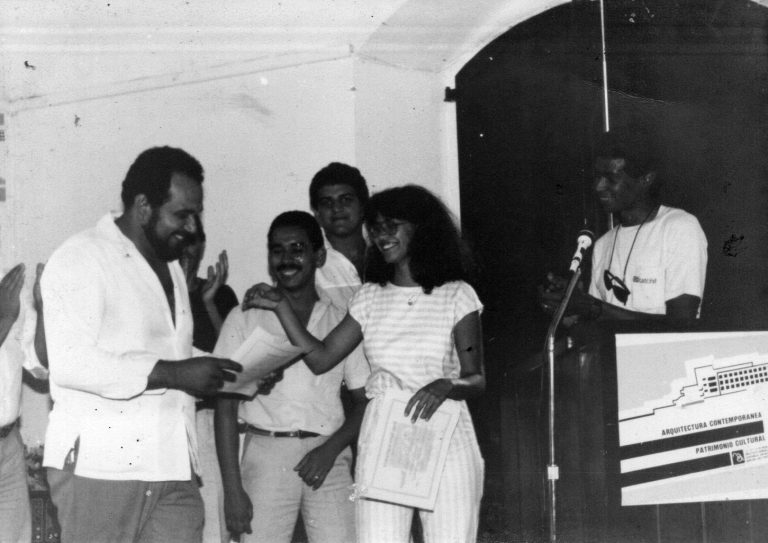

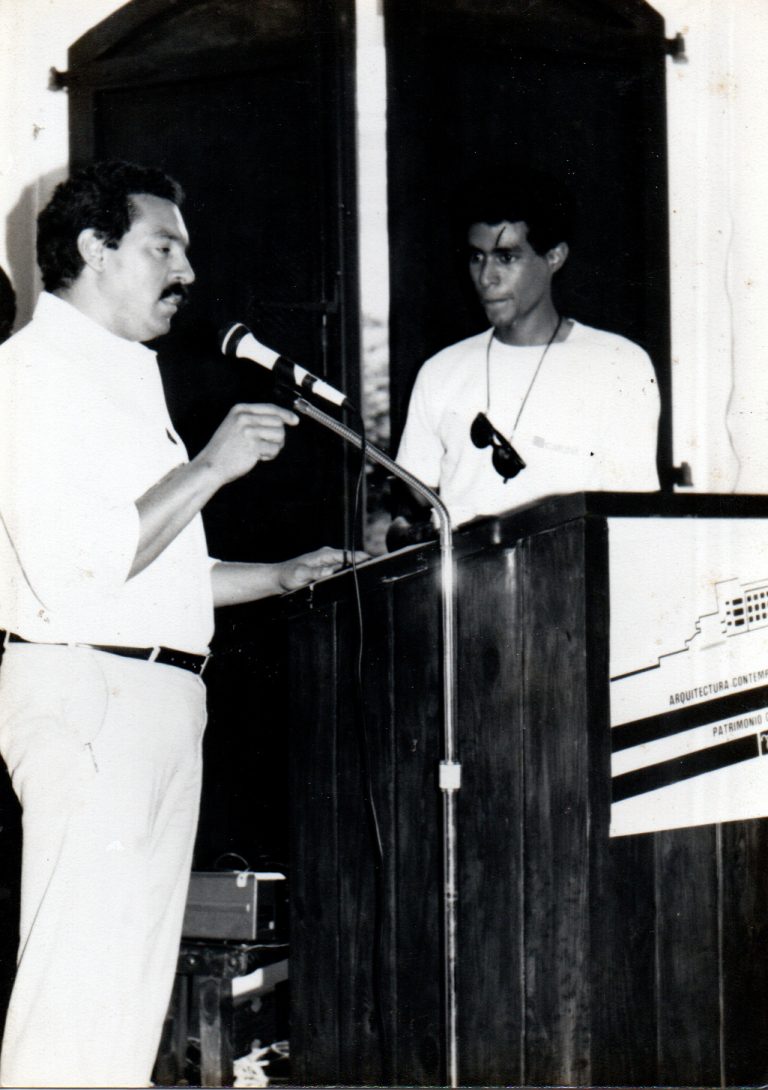

By mid 1984, the press caught wind of the plans to tear down the old Jaragua building... and yet the Transamerican contract still hadn't gone through Congress for approval. Motivated by the possibilities of this legal limbo, several civilian groups came together to try to stop the massacre. This list included journalists, architects and architecture students, as well as the members of Grupo Nueva Arquitectura, who sent a formal request to local legislators to declare the hotel part of the country's design heritage. That November 14, at the City Hall, councilor (and architect) Joaquín Gerónimo did officially declare it a work of cultural heritage, sending his proposal to the Executive Branch in order to try to halt the plans that wanted to see the old building fall in order to build a new complex.

Public opinion has some differing opinions

THE VOICES

The debate around the potentially upcoming demolition has been preserved in hundreds of articles, op-eds and paid spaces that were published in nationwide newspapers. For example, at El Nacional Bolívar Díaz Gómez asked:

-

A September 20, 1984 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A September 23, 1984 clipping from El Nacional (Source: AGN)

-

An October 6, 1984 clipping from El Nacional (Source: AGN)

-

An October 31, 1984 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A December 11, 1984 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A January 20, 1985 clipping from Listín Diario (Source: AGN)

-

A January 23, 1985 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

A January 25, 1985 clipping from Última Hora (Source: AGN)

-

A February 3, 1985 clipping from El Nacional (Source: AGN)

-

A February 6, 1985 clipping from El Nacional (Source: AGN)

Fire in the whole building

-

A January 19, 1985 clipping from Última Hora (Source: AGN)

-

A January 21, 1985 clipping from Hoy (Source: AGN)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

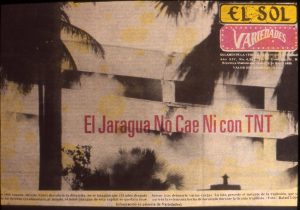

A March 14, 1985 clipping from El Sol (Source: AGN)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

The hotel's demolition process in 1985 (Source: Lidia León)

-

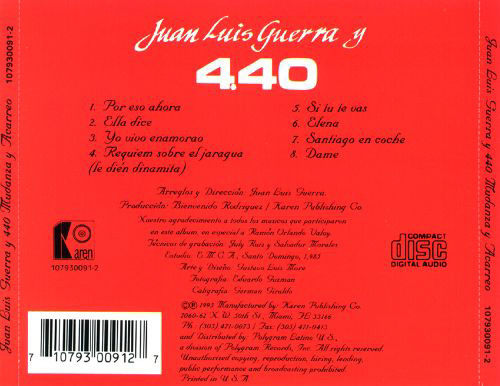

Requiem sobre el Jaragua, a song written by Juan Luis Guerra

1985

Courtesy of Karen Records

THE RAZING

As the calendar marked March of 1985 and the debate about Jaragua's future went on, the hotel stood completely empty, ready to be demolished. Although Congress still hadn't approved the contract, Transamerican began by tearing down the south façade of the building... but that drove such a media frenzy that they had to put a stop to those works. // Martínez Burgos y Asociados, a building contractor, had hired Cocimar to handle the demolition itself, and Cocimar then hired Dykon, an American company specialized in explosives. And so, on the afternoon of March 13 people resigned themselves to witnessing the much-hyped spectacle of a Hollywood-style explosion, since authorities explained that the building was in such dire conditions due to the impact of four decades of saltpeter that it could tumble down on its own without warning. And yet, when those two thousand loads of TNT went off, the Jaragua Hotel barely moved a few inches... there stood Guillermo González's masterpiece, nearly intact, seemingly taunting those who dared called it a weak white elephant. Unfortunately, as dynamite failed to do its job, Transamerican's plans continued and they gave the building an ingnominious death, using a wrecking ball and even using pickaxes.

Our lost heritage (and the one we're about to lose)

-

Henry Gazón Bona's Matadero Industrial, built in Santo Domingo in 1942 (Source: AGN)

-

José Manuel "Nani" Reyes' Nader Residence, built in Santo Domingo in 1966 (Source: Francisco Manosalvas - Arquitexto)

-

José Antonio Caro's Palacio de Correos, built in Santo Domingo in 1956 (Source: Caro Family Archives)

-

Tomás Auñón and Joaquín Ortiz's Molinari Residence, built in Santo Domingo in 1941 (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

-

The Copello Building in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2019 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

-

A state of abandonment in Gazcue, pictured in 2021 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

The 1915 Morey Building, built by Antonio Morey Castañer in San Pedro de Macorís, pictured in 2021 (Source: Jorge González)

-

The 1929 Díez Building, built by Benigno Trueba in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2021 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

THE FALLEN

In a country that has only been taught to appreciate one type of architectural heritage —that is, a colonial one— our built testimony of the 20th century is often misunderstood and unaprecciated. Things get more complicated once we take into account the shared role of our architects, the authorities, our real-estate developers and the homeowners who show little to no sensitivity to fight for its preservation. Who's crazy enough to preserve a crumbling Gazcue manor when one can instead plant an apartment building, its aesthetic value notwithstanding?

That explains why a large part of our modern heritage can be found modified, maimed and even abandoned... while another part has already disappeared. Just like the Jaragua Hotel went down, so did the Molinari House by Tomás Auñón and Joaquín Ortíz. So did the Matadero Industrial by Henry Gazón Boná. So did the Secretary of State for Health and Education and the Workers' Hospital Dr. William Morgan, both designed by Marcial Poy Ricart. So went the Schad and Pichardo Ricart houses, some of the first samples of residential rationalism presented by Guillermo González.

In spite of this long list, we still have a bundle of architectural heritage items about to the lost which, if we come to our senses collectively, we can still save. The Centro de los Héroes sees how its Venezuelan Pavilion, by Alejandro Pietri, is at risk of tumbling down. On El Conde Street stands González's Copello Building, as well as the Díez and Baquero buildings, both created by Benigno Trueba y Suárez. In San Pedro de Macorís there's the Morey Building by Antonio Morey Castañer. Santiago de los Caballeros still has its abandoned Mercedes Hotel, designed by Romualdo García Vera. These projects can still return to the glory of days past via a series of interventions that can provide a productive use. An intelligent readaptation is, indeed, the name of the game here.

Lest we lose more Jaraguas

THE HOPE

Just like our authorities have made the effort to revitalize the properties inside the Colonial City, using both legal and economic tools, likewise they should acknowledge the cultural (and eventually touristic) value of our modern heritage. That's why we finally need Congress to pass our Heritage Law, an important element that has been stuck in legislative limbo for more than a decade. Without it, we'll keep seeing how other Jaraguas will just keep on crumbling. // Nevertheless, as long as we socialize the stories of those who stepped inside the hotel during its golden and silver years, as we honor the work of Guillermo González and as our local architecture faculties recognize both the trajectory and the potential of Dominican design, that Jaragua, indeed, won't crumble.

-

The 1945 Peña-Batlle Residence, currently UNIBE's headquarters, designed by Amable Frómeta in Santo Domingo (Source: UNIBE)

-

Mario Lluberes's García Trujillo House, currently the National Judicial College in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2021 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

-

An aerial view of the urban complex built in 1955 for the Fair for Peace and Fraternity in the Free World, today the Center of the Heroes of Constanza, Maimón and Estero Hondo in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2018 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

Villa Hena, also called Casa de las Raíces, built by Zoilo Hermógenes García in Santo Domingo in 1914, pictured in 2021 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

The former headquarters of the Central Bank of the Dominican Republic, built by José Antonio Caro in Santo Domingo in 1956 (Source: Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana)

History repeats itself across the sea

-

The 1955 Agua y Luz Theater, designed by Carles Buïgas in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2018 (Source: Elizabeth Esquea and Eliezer Ramírez)

-

The 1955 Agua y Luz Theater, designed by Carles Buïgas in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2021 (Source: Alex Martínez Suárez)

-

The 1955 Agua y Luz Theater, designed by Carles Buïgas in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2018 (Source: Elizabeth Esquea and Eliezer Ramírez)

-

The 1955 Agua y Luz Theater, designed by Carles Buïgas in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2018 (Source: Elizabeth Esquea and Eliezer Ramírez)

-

The 1955 Agua y Luz Theater, designed by Carles Buïgas in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2018 (Source: Elizabeth Esquea and Eliezer Ramírez)

-

The 1955 Agua y Luz Theater, designed by Carles Buïgas in Santo Domingo, pictured in 2018 (Source: Elizabeth Esquea and Eliezer Ramírez)

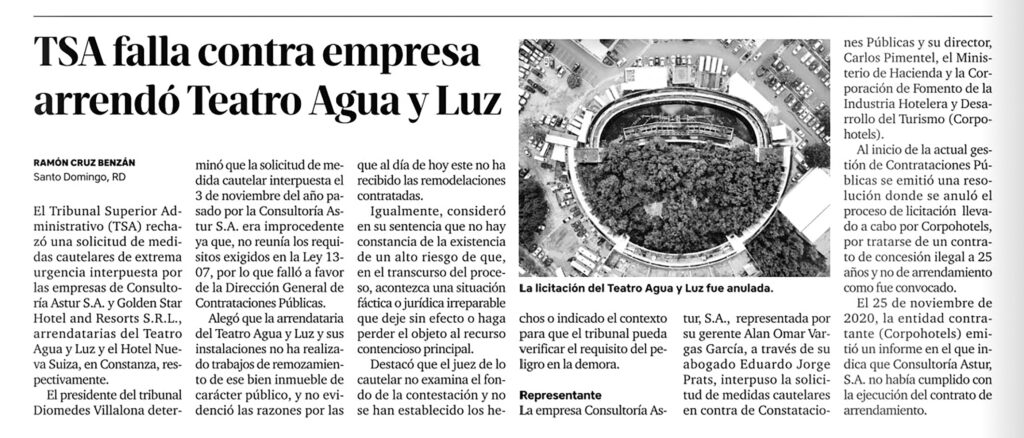

THE ALERT

The Teatro Agua y Luz, designed by Catalonian architect Carles Buïgas i Sans for 1955's Fair for Peace and Fraternity in the Free World, is going through a process similar to the hotel's final years. Unfortunately, a dubious series of contracts and its unprotected state for more than a decade have turned it into a strong candidate to become our next Jaragua. Will this be the generational catalyst Millennial architects and design professionals need? Will this be the example that will force us to acknowledge how we're failing both our city and our citizens? Are we willing to fight to stop the few Jaraguas we have left from crumbling?